Beyond blended: rethinking curriculum and learning design

Helping curriculum teams consider the pedagogic differences between in place and online learning, and the need to balance flexibility with the specific needs of students.

The need for new approaches

In 2022, following the disruptions of the pandemic, we felt it was timely to consolidate our understanding of the different benefits and challenges of online learning, and the value of in place learning (where learners and educators are physically present in the same space). We wanted to align this with existing thinking and research on how best to integrate technology into the curriculum through design, content creation and teaching methodologies.

Higher education (HE) sector experiences during the pandemic offered an opportunity to consider the whole curriculum, the notion of students being in place at university and the value of both online and in place learning, teaching and assessment (LTA). They also presented a chance to highlight what we learned during our wholly online experiences and acknowledge that universities and curriculum teams already have a lot of the expertise they need to navigate and adapt to various challenges.

Our 2022 report on approaches to curriculum and learning design across UK higher education offered a review of learning and curriculum design across the HE sector. It highlighted a pre-pandemic focus on activities and resources, particularly around enhancing and encouraging use of the virtual learning environment (VLE), with learning design focusing on tasks and sequencing. Support for media production (eg lecture recording, video and audio content) was a clear focus, as well as how students and learners were using digital devices to access resources, to produce notes and maybe develop their skills in some generic software.

Post-pandemic, we are looking at a more holistic, whole curriculum approach to design. There's been a clear focus on different modes of participation and on trying to be as flexible as we can for both students and staff.

“The Jisc ‘beyond blended’ project and associated report is a comprehensive analysis of the current state of play in a post-pandemic higher education sector. Even though every institution will take forward ‘blended’ slightly differently, this report acts as a robust starting point for localisation and draws upon experts and knowledge from across the sector to set out a strong foundation.”

Professor Simon Thomson, director of flexible learning, University of Manchester

Downloadable resource: Post-pandemic curriculum design: a summary (pdf)

This table provides a summary of some of the differences between pre-and post-pandemic curriculum design.

Related resources

Going beyond blended learning

Moving forward from previous notions of blended learning, we are now talking about major alternatives that are available to curriculum designers and to students as choices about how to participate in a particular activity or module or part of the curriculum.

"We're talking about the blend between live classes and independent study time, synchronous and asynchronous, or responsive and reflective time in the curriculum. And thinking about how particular technologies, for example, the lecture recording or the collaborative learning environments – ‘bend time’ in the curriculum because they allow both live participation and independent study to be coordinated around the same space."

Helen Beetham, researcher at University of Wolverhampton and Sheila MacNeill, consultant

Listen to our podcast: Beyond the Technology: demonstrating digital transformation - beyond blended - post-pandemic curriculum and learning design

Elizabeth Newall welcomes Helen Beetham and Sheila MacNeill to discuss rethinking learning and curriculum design in higher education in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the need to adapt to new challenges.

A beyond blended approach considers what is being blended, what choices are available and then what is the pedagogic value of those choices, so we can talk to students about the value to them of engaging in certain ways.

Our 2023 beyond blended report offered lessons from the HE sector on post-pandemic curriculum and learning design. It highlighted a need for a shared vocabulary between curriculum design teams. There were a lot of words in that space such as ‘hybrid’, ‘hyflex’, ‘flexible’, ‘blended’ that were not always being used in a clear enough way to allow the conversation to be student-centred, or to allow that conversation to really centre the curriculum.

Our research identified some increasingly important issues for curriculum design:

- All times/spaces of learning are (potentially at least) blended, but online and in person are different pedagogic spaces; integrating them (especially live) demands new skills and often more resources

- Learners/teachers expect choice and have different preferences and needs (issues of pace, attention management, sociability, presence). Student engagement must be addressed to consider new requirements

- Learners differ in their management of asynchronous time (self-efficacy, time and task management) – this time needs to be explicitly represented

- Digital technologies create new relationships to space and to time (eg recording, platforms for collaboration and iteration, hybrid live/asynchronous spaces)

- Role of artificial intelligence (AI) both in production of the curriculum (eg lesson plans) and in student production of learning outcomes

In a beyond blended approach to curriculum design we consider the two blends of time (asynchronous and synchronous) and place (in place and/or using an online platform). In addition to the more traditional learning design issues like activity, task, technology and materials. We suggest stepping back and thinking:

- What time and place will this activity happen in?

- What choices do students have or not have about that?

- How do we make materials and activities available?

- Which platforms do students choose to collaborate with, or to access?

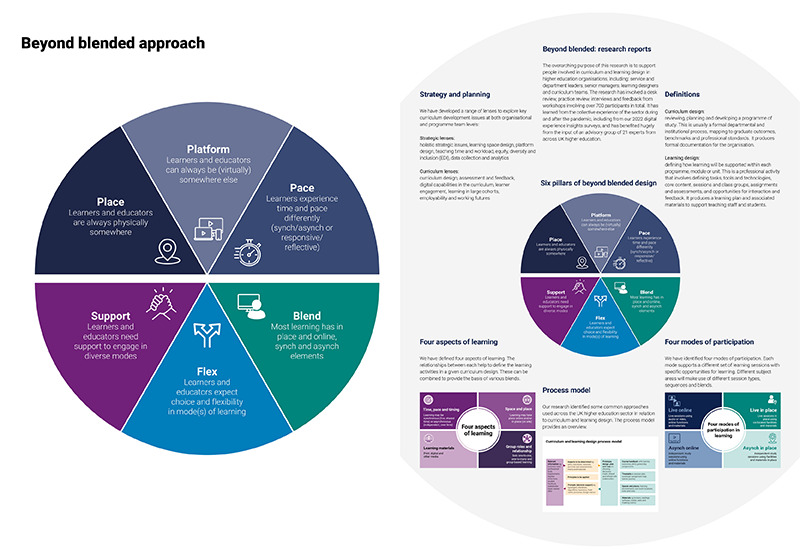

The beyond blended report described:

- Four aspects of learning

- Four different modes of participation in learning

- Six pillars or precepts for curriculum design in the four modes

“I am extremely supportive of pedagogy-led vocabulary used in the report. I believe the sector needs to have a shared set of terminology that can be easily understood by teaching staff to achieve a responsive strategy for curricula development.”

Alyson Hwang, researcher at Policy Connect, lead researcher for the Higher Education Commission’s inquiry into blended learning

This guide offers a simple vocabulary for describing modes of learning and considers some key questions around how these contribute to student learning and engagement. It is equally important to take these conversations forward from the curriculum space into the institutional space to consider strategic aspects such as platform procurement considerations, what kinds of physical spaces are needed, and what kinds of flexibility should be offered. These wider organisational aspects are critical as organisations adopt more strategic approaches to digital transformation.

Definitions

Curriculum design: reviewing, planning and developing a course of study. This is usually a formal departmental and institutional process, mapping to graduate outcomes, benchmarks and professional standards. It produces formal documentation for the organisation.

Learning design: defining how learning will be supported within each course, module or unit. This is a professional activity that involves defining tasks, tools and technologies, core content, sessions and class groups, assignments and assessments, and opportunities for interaction and feedback. It produces a learning plan and associated materials to support teaching staff and students.

The terms are often used interchangeably in UK HE, and the two design processes in any case overlap or iterate. For example, feedback from learning in practice (how did learners experience these activities or meet the learning outcomes?) should inform the next iteration of development. So we use the term curriculum and learning design to mean all the processes of reviewing, planning and designing a programme of study and how students will learn within it.

Applying the beyond blended resources

If you are already familiar with our beyond blended research and materials you may like to go straight to the section on using the beyond blended materials: alternative approaches for different perspectives. This section offers a series of different lenses on the six pillars, which provide useful prompts around a range of strategic and curriculum approaches.

Let us know how you are using the beyond blended resources at your institution. Fill in our beyond blended resources feedback form.

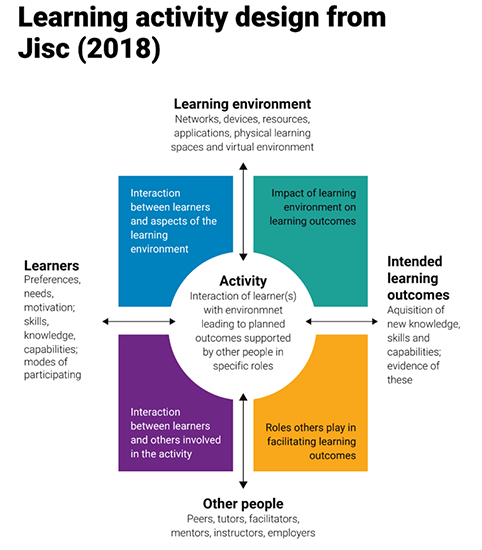

Four aspects of beyond blended learning

We have many options when designing the curriculum or learning activities, and different contextual aspects affect the choices we make about what, when, where and how we blend these options. These include: subject discipline requirements, teaching frameworks, assessment criteria, teaching approaches, practical considerations, culture and traditions, resources available and student needs and expectations.

We need to draw on both established research and new thinking to understand why a particular session might be delivered live and online rather than self-directed and in place, or how these two sessions might complement each other. It is particularly important to understand how different sessions can be designed to engage students actively in their learning.

We have used the term ‘in place’ to describe when learners and educators are co-located (usually, but not always, on campus). In contrast, ‘online’ learning describes when participants come together in the same digital platforms without the need to be present at the same location.

Downloadable resource: Comparing in place and online learning sessions (pdf)

This table compares the two modes of learning for learning experience, pace and presence, classroom culture, layout and facilities, active engagement, group work, and notes and records.

In place and online learning environments come with a range of facilities, functions and materials. These can be encountered synchronously (meaning live, at the same time, in shared or timetabled time) or asynchronously (meaning at different times, usually within a time window such as a teaching week or an assignment timeframe).

Downloadable resource: Comparing live and asynchronous learning time (pdf)

This table compares live and asynchronous learning for the learning experience, locus of control, typical locations, group work, and typical assessments.

Digital modes of learning can blur what were once clear boundaries, creating intermediate settings. Digital media can bend time boundaries as well as offering new experiences of space. This means students and educators must negotiate new choices and trade-offs, as well as situations where expectations may be unclear, and make choices on how to blend these various options. Some can be planned ahead while others may be made as a programme of study progresses or as student circumstances and needs change. We offer a range of practical materials to help consider factors affecting these choices around time, pace, place and platform.

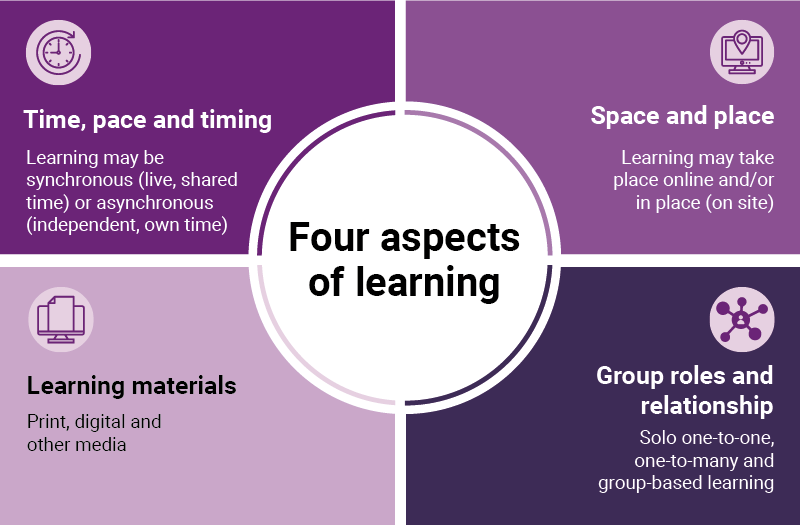

The four aspects of learning

Alt text for the four aspects of learning graphic

A graphic showing the four aspects of learning. There are four quadrants.

- The top left quadrant: Time, pace and timing - Learning may be synchronous (live, shared time) or asynchronous (independent, own time)

- Top right quadrant: Space and place - Learning may take place online and/or in place (on site)

- Bottom left quadrant: Learning materials - Print, digital and other media

- Bottom right quadrant - Group roles and relationship - Solo one-to-one, one-to-many and group-based learning

A graphic showing the four aspects of learning. There are four quadrants.

- The top left quadrant: Time, pace and timing - Learning may be synchronous (live, shared time) or asynchronous (independent, own time)

- Top right quadrant: Space and place - Learning may take place online and/or in place (on site)

- Bottom left quadrant: Learning materials - Print, digital and other media

- Bottom right quadrant - Group roles and relationship - Solo one-to-one, one-to-many and group-based learning

These four aspects of learning can be blended in many ways:

- Time, pace and timing: synchronous (live, shared time) and asynchronous (independent, own time)

- Space: place and platform

- Learning materials: tools, facilities, learning media and other resources (digital, print-based, other materials)

- Groups, roles and relationships: teacher-led and peer learning, varieties of group learning

In relation to learning content, materials were traditionally print-based (text or graphical). Both live classes and own-time study now involve the use of digital resources far more than print – e-books, e-journals, presentation slides, videos, digital maps and timelines, digital notes and annotations.

Digital environments can change the meaning and the learning potential of interactions in many ways. These can be impacted by many variables such as learner preferences and needs, experience and competence in communicating and/or collaborating digitally, and different curriculum and teaching approaches.

Other aspects can be considered and may even be 'blended': for example student-led and teacher-led learning.

Tips and ideas

Think beyond traditional session types. Rather than trying to ‘translate’ existing sessions into an online mode, look at how new activities and session types are emerging, and how digital technologies can expand notions of time and space.

Think of time and place as resources that link curriculum needs with organisational processes (room allocation, timetabling…).

Focus on high value space/time combinations for learner engagement – explain the value clearly, in terms that will make sense to students.

Remember to get informal and formal feedback from your students around the space/time combinations that work for them.

Different modes and blends provide settings for different activities and interactions – the modes approach complements, but does not replace, a focus on learning activity.

Downloadable resource: Exploring the four aspects of designing beyond blended learning (pdf).

Find out more about the four aspects of designing beyond blended learning, including considerations and examples.

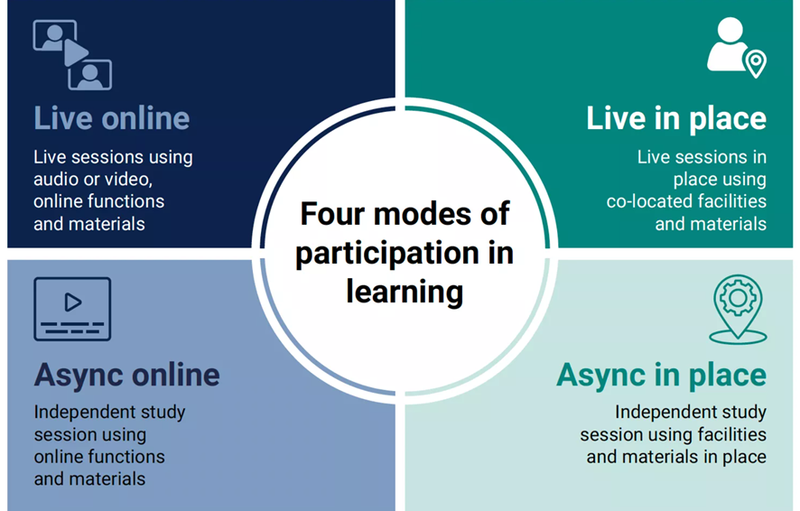

Four modes of participation in learning and session types

When considering the four aspects of learning the last two, learning materials and groups, roles and relationships can often be decided flexibly and collaboratively as learning unfolds. The first two, time and pace and space and time, shape the overall design of the curriculum and require some forward planning.

The practical resources in this guide illustrate some of the educational reasoning to help you plan a particular blend of modes across diverse sessions and activities.

We have identified four possible modes of participation in learning that shape every session, activity and interaction. They are:

- Online and synchronous (live)

- In place and synchronous (live)

- Online and asynchronous (independent)

- In place and asynchronous (independent)

Alt text for four modes of participation in learning graphic

A graphic showing the four modes of participation in learning. There are four quadrants.

- Top left quadrant: Live online - live sessions using audio or video, online functions and materials

- Top right quadrant: Live in place - live sessions in place using co-located facilities and materials

- Bottom left quadrant: Asynch online - independent study sessions using online functions and materials

- Bottom right quadrant: Asynch in place - independent study sessions using facilities and materials in place

A graphic showing the four modes of participation in learning. There are four quadrants.

- Top left quadrant: Live online - live sessions using audio or video, online functions and materials

- Top right quadrant: Live in place - live sessions in place using co-located facilities and materials

- Bottom left quadrant: Asynch online - independent study sessions using online functions and materials

- Bottom right quadrant: Asynch in place - independent study sessions using facilities and materials in place

Tips and ideas

Understand the four modes as pedagogic resources when planning activities – what works for your students, your subject area and your setting? Can you share them with students to help them understand your expectations around their participation?

Session types

Each participation mode supports a different set of learning sessions with specific opportunities for learning. Different subject areas will make use of different session types, sequences and blends.

Downloadable resource: Session types in the four modes of participation (pdf).

This table summarises examples for synchronous in place sessions, synchronous online sessions, asynchronous in place sessions and asynchronous online sessions.

Curriculum design workshop cards

Our PowerPoint slideshow offers more detail for sessions in each of the modes describing features, pedagogical benefits, platform/place, facilities/functions and typical activities and interventions.

These session type ‘cards’ can be downloaded and used in a curriculum design workshop or course meeting to:

- Plan sessions and activities

- Consider a wider range of session types

- Ensure a balance of session types to meet different needs

- Describe new session types and activities (beyond those described here)

Beyond blended posters

We developed a series of posters to illustrate modes of student participation across different spaces, places and times. They provide a simple, graphical overview of how the four aspects of the beyond blended approach (place, time and pace, learning media resources, groups roles and interactions) work for different types of activities across the four different modes of participation (sync in place, sync online, async in place, async online). The posters offer a range of examples:

- Live lecture: in place/off campus

- Personal study time: on campus/off campus

- Lecture recording

- Collaborative design activity

- Activity type(s)

- Platform type(s)

The posters have been designed as flexible resources that can be integrated with existing design frameworks. You can use them as starting points for discussions with a range of key stakeholders including students, programme/course design teams, learning space working groups, library, estates, IT and other professional services. They can help to describe, share and develop common understanding of the current context as well as help to develop the ‘what will be’ in relation to student engagement and the development of beyond blended approaches.

They could be used as starting points for discussions around questions such as:

- What can I do with this technology before, during and after class?

- What can I do with this session (thinking about time and place)?

- What are we trying to achieve (beyond ‘learning outcomes’)?

- How can I help students to learn effectively in this setting?

- How do students use this space?

- What do students need to use this space effectively?

While they can be used in one-off sessions with groups of students, a more consistent and wide-reaching approach could be achieved if the organisation incorporates them into a programme of activities to support student digital learning capabilities.

Suggestions and contexts for using the beyond blended posters:

Student induction

As part of the induction process, the posters can help students understand expectations of where, when, how and what they will be doing during particular activities and how they are expected to engage in learning and assessment activities. This can be particularly useful for international students to help them quickly see expected modes of participation, which may differ from their previous educational experiences.

As part of the induction process, the posters can help students understand expectations of where, when, how and what they will be doing during particular activities and how they are expected to engage in learning and assessment activities. This can be particularly useful for international students to help them quickly see expected modes of participation, which may differ from their previous educational experiences.

Student co-creation/feedback

The posters can also help students understand where and when they currently engage with activities, their expectations and understanding of different modes of participation, the platforms/spaces that they actually use. They can provide an additional way for students to engage with various aspects of curriculum and learning design.

The posters can also help students understand where and when they currently engage with activities, their expectations and understanding of different modes of participation, the platforms/spaces that they actually use. They can provide an additional way for students to engage with various aspects of curriculum and learning design.

Programme/module teams/individual staff members

Additionally, you can use the posters with groups of staff (or individual members of staff) as part of formal and informal design sessions or conversations, to help map and develop shared understandings of how the four aspects of the beyond blended approach (place, time and pace, learning media resources, groups roles and interactions) work for different types of activities across the four different modes of participation. Introduced at the start of a session/design process, they can encourage feedback in a relatively short space of time, or they can be a more integrated resource to aid with designing activities.

Additionally, you can use the posters with groups of staff (or individual members of staff) as part of formal and informal design sessions or conversations, to help map and develop shared understandings of how the four aspects of the beyond blended approach (place, time and pace, learning media resources, groups roles and interactions) work for different types of activities across the four different modes of participation. Introduced at the start of a session/design process, they can encourage feedback in a relatively short space of time, or they can be a more integrated resource to aid with designing activities.

With other professional services

Lastly, the posters can be used by (and with) professional services teams (including but not limited to, library, IT, estates, timetabling, quality) to develop shared understanding of how different organisational spaces (in place and online) are being used, and the evolving pedagogical, time and technical requirements of different spaces.

Lastly, the posters can be used by (and with) professional services teams (including but not limited to, library, IT, estates, timetabling, quality) to develop shared understanding of how different organisational spaces (in place and online) are being used, and the evolving pedagogical, time and technical requirements of different spaces.

Downloadable resources:

We also provide blank versions of the posters that can be adapted and/or expanded on depending on your own context.

Six pillars for designing ‘beyond blended’ learning

"As we emerge from the pandemic, both students and educators are struggling to navigate their way through a world that presents a bewildering number of possibilities for how to learn. The six pillars for curriculum design, together with prompts to frame our thinking, will help to inform decisions about how and where to deploy resources that will be useful to strategic planning in universities. Others will help educators to engage with students in designing meaningful learning activities that employ technologies that enhance the student experience."

Professor Katharine Reid, faculty of science associate pro-vice chancellor for education and student experience, University of Nottingham

Working closely with our advisory group and workshop participants we have developed a simple set of precepts or ‘pillars’ for curriculum design in the four modes of participation in learning. These are not intended to replace other principles and frameworks, but to be used alongside them.

The pillars can be referenced early in the curriculum design process, when considering the overall shape of the curriculum, the number and type of sessions and the learners’ journey through place and platform, live time and independent study. You can also use them near the end of curriculum review to check back that the questions we pose have been asked, even if the answers are still emerging. And, finally, they can be used in dialogue with other strategic processes, to ensure alignment.

The six pillars are:

- Place: learners and educators are always physically somewhere

- Platform: learners and educators can always be (virtually) somewhere else

- Pace: learners experience time and pace differently (synchronous/asynchronous or responsive/reflective)

- Support: learners and educators need support to engage in diverse modes

- Flex: learners and educators expect choice and flexibility in mode(s) of learning

- Blend: most learning has in place and online, synchronous and asynchronous elements

Downloadable resource: Beyond blended guide (pdf)

Our beyond blended guide features the six pillars on one side and on the other side is a wheel describing the different aspects of beyond blended: definitions, session types, process model, modes of participation, strategy and planning. This prints in A3 format.

Six pillars: place

Learners and educators are always physically somewhere.

Learning and teaching are activities grounded in physical spaces. Regardless of the form that education takes, whether it is traditional classroom settings, online learning environments or informal educational contexts, learners and educators both occupy a specific physical location while learning and teaching. This could be a university campus, a home office, a library, a coffee shop or even various outdoor settings.

The physical environment plays a crucial role in the educational experience, influencing factors such as accessibility, comfort, available resources and how conducive the overall atmosphere is to learning and teaching. The physical presence of learners and educators in a shared space can also foster interaction, collaboration and a sense of community.

Some curriculum design questions to consider about place:

- Where are our learners in each session, and across a typical learning week? How does this pattern suit their needs?

- What do learners need in place for each aspect of their learning?

- What is the value of co-presence in this particular learning? How are we maximising that value?

- Can learning spaces be reconfigured, or do we have access to a variety of spaces to suit different requirements?

- What makes it difficult for learners to be physically present and how are we helping? What are the needs of different groups of students eg international students, commuter students?

Six pillars: platform

Learners and educators can always be (virtually) somewhere else.

Virtual platforms enable learners and educators to transcend physical boundaries and engage with educational content, resources and communities from almost anywhere. The dynamic and flexible nature of virtual presence allows for a diverse range of learning experiences. Learners and educators can connect, interact and share knowledge through formal courses, online events and collaborate with peers globally through digital tools. Educators can reach a broader audience, incorporate a variety of multimedia and interactive resources into their curriculum, experiment with innovative teaching methods and collaborate with peers and experts globally.

Virtual environments can allow learners to explore subjects at their own pace and according to their interests, and they offer potential to enhance the educational experience. This virtual mobility in education fosters a more inclusive and accessible learning environment, where knowledge and learning opportunities are not limited by a person's physical location.

Some curriculum design questions to consider about platform:

- What generic platforms are provided and what specialist platforms, apps and online communities do we ask students to access?

- What alternatives are students choosing and why?

- What is the value of virtual participation for learning in this programme and how are we maximising that value?

- What makes students want to engage online?

- What makes it difficult for learners to participate fully online and how are we helping?

Six pillars: pace

Learners experience time and pace differently (synchronous/asynchronous or responsive/reflective).

Learners can engage with and process educational content in a variety of ways. In synchronous learning learners and educators interact in real time, such as in traditional classroom settings or live online classes. This environment is often responsive, requiring immediate engagement and interaction. Learners must keep pace with the instructor and their peers, which fosters a sense of community and immediacy but potentially limits individual reflection and processing time.

In contrast, asynchronous learning allows learners to engage with material at their own pace, in their own time. It offers learners the opportunity to digest information, reflect, think critically and apply knowledge without the pressure of immediate response. Asynchronous learning can be particularly beneficial for those who need more time to understand concepts or who juggle their education with other responsibilities. Both synchronous and asynchronous learning approaches offer distinct advantages and cater to different needs, emphasising the importance of flexibility and choice for learners.

Some curriculum design questions to consider about pace:

- What different kinds of session (synchronous/asynchronous) are offered for different aspects of learning?

- How are these timetabled across the week to provide a predictable rhythm and to support good study habits?

- How do we ensure that live sessions are used to maximum value?

- How does independent, reflective study time support learners to develop self-direction?

- What different kinds of assessment are scheduled (eg live, time-limited, extended) and how are they timetabled to avoid overload?

Six pillars: blend

Most learning has in place and online, synchronous and asynchronous elements.

The integration of both in place (physical) and online components, along with a mix of synchronous and asynchronous elements, creates a multi-faceted educational environment that can support a wide range of learning preferences and needs. In this approach learners can engage in real-time, in-person interactions during physical classes or lectures, benefiting from immediacy and communal aspects of learning. They can also be provided with online resources and digital platforms where they can access course materials, participate in discussions and complete assignments at their own convenience.

This combination of in place and virtual learning experiences allows for a dynamic and adaptable educational experience. Incorporating both synchronous and asynchronous approaches ensures that learners can benefit from structured, real-time engagement as well as thoughtful, individual exploration and reflection. It is a comprehensive approach to blending that recognises the diverse needs of learners and offers a more inclusive and versatile learning environment.

Some curriculum design questions to consider about blend:

- How are curriculum resources (tasks, materials, interactions) distributed in a range of session types (sync/async)?

- How are places and platforms combined to support different activities, including assessment activities?

- How is the value of different modes explained to learners?

- How do we help learners to use their own digital devices and resources, as appropriate?

Six pillars: flex

Learners and educators expect choice and flexibility in mode(s) of learning.

Learners increasingly seek options that allow them to tailor their educational experiences to their personal and professional lives, preferring a mix of in-person, online, synchronous and asynchronous learning opportunities. This flexibility enables students to balance education with other commitments, such as work or family, and to engage with material in ways that suit their learning preferences and pace.

Educators need to adapt to changing expectations by employing a variety of teaching strategies and technologies that support different modes of learning. They recognise the value of offering choices to enhance engagement, motivation and success across their diverse student cohorts. HE organisations that provide this level of choice and flexibility are better positioned to meet the evolving needs of their learners, fostering a more inclusive and effective educational environment.

Some curriculum design questions to consider about flex:

- When are decisions made about modes of participation and who makes them (eg programme team, cohort teacher, individual learner)?

- What choices do learners have about how they participate and what are the trade-offs (eg staff workload, loss of cohort effects)?

- How is engagement sustained in different modes?

- How do learners integrate their learning across different modes (eg notes, task outcomes)?

- What choices do learners have in how they are assessed?

- Is assessment well matched with modes of learning and teaching?

Six pillars: support

Learners and educators need support to engage in diverse modes.

Both learners and educators need support to navigate diverse modes of participation in learning effectively. Learners, with varying backgrounds, abilities and requirements, require guidance and resources to adapt and thrive in these varied educational settings. This support can include access to digital tools for online learning, personalised assistance for those with special needs, or strategies to develop self-directed learning skills. They need appropriate support at various stages of their course to build on their digital capabilities to become effective digital learners.

Educators may need professional development and support before they can facilitate diverse learning experiences effectively, incorporating both digital capability and pedagogical innovation. They may also require support in creating inclusive and engaging learning environments that cater to the diverse needs of their students.

Some curriculum design questions to consider about support:

- What devices and skills do learners need to engage fully in this learning?

- How are skills practised and supported in the curriculum? How are individual needs identified?

- Have we identified the time and workload associated with each element of the curriculum and allocated staff appropriately?

- How are staff supported with any additional skills to manage teaching in diverse modes?

Downloadable resources:

This table lists curriculum and strategic prompts for place, platform, pace, blend, flex and support.

Using the beyond blended materials

Alternative approaches for different perspectives

“The pillars and lenses devised by Jisc provide a framework in which to base our day-to-day conversations with academic staff and our students through to bespoke learning design interventions. Curriculum design is complex and needs to ensure that a myriad of approaches and considerations are made; the pillars and lenses encourage and facilitate this thinking by ensuring that all the relevant concepts are explicitly considered within an institution’s design framework.”

Kate Coulson, associate dean for assessment, BPP University

All the beyond blended approaches and materials can be used in a range of ways as appropriate for different contexts. We have highlighted which materials might be most useful for each stage. The materials can support strategic organisational level conversations and they are useful for different stages of curriculum review and design processes.

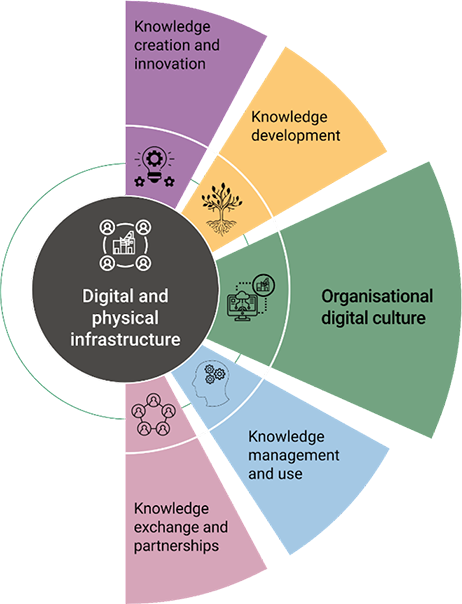

Strategic approach to beyond blended

Designing ‘beyond blended’ learning requires a strategic approach that considers a range of factors and supports informed decision making. The prompts in our strategic lenses align with Jisc’s framework for digital transformation in higher education, which offers a structure to support a shared understanding of digital transformation across a higher education organisation. The framework identifies strategic goals for a wide range of activities, as well as examples of how organisations might work towards those aims. The framework is part of a wider digital transformation toolkit that includes a comprehensive maturity model for each area as well as roadmap and action planning templates.

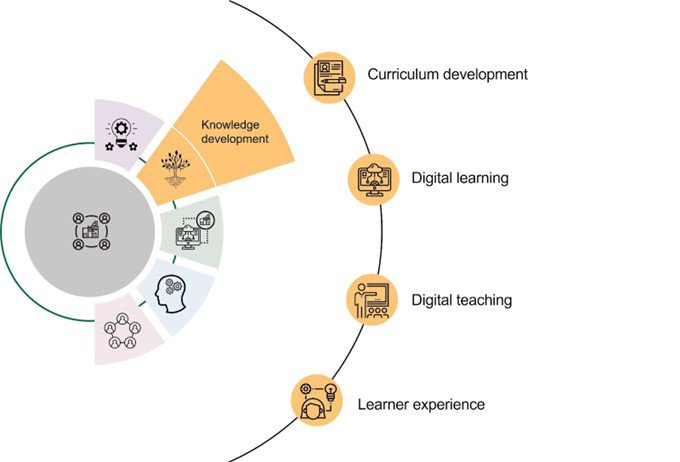

Alt text for digital transformation framework graphic

Framework for digital transformation: knowledge creation and innovation, knowledge development, organisational digital culture, knowledge management and use, knowledge exchange and partnerships, digital and physical infrastructure

Framework for digital transformation: knowledge creation and innovation, knowledge development, organisational digital culture, knowledge management and use, knowledge exchange and partnerships, digital and physical infrastructure

The knowledge development area of the framework maps directly to curriculum and learning design as it includes four aspects:

- Curriculum development

- Digital learning

- Digital teaching

- Learner experience

Other areas of the framework relate to some of the wider strategic aspects of beyond blended design that need to be considered:

- Organisational digital culture includes digital culture and mindset (including digital capability), organisational identity, organisational wellbeing and organisational change

- Digital and physical infrastructure includes digital infrastructure, connectivity, cybersecurity, digital support and estates management

- Knowledge management and use includes information and data literacy, learning analytics and library services

You may find the digital transformation toolkit useful to help articulate any problems you are trying to address or to identify ways to support developments or investment that might be needed to achieve curriculum and learning design goals. The toolkit may also be useful to help you consider the prompts included in the strategic and curriculum lenses.

Strategic lenses

We have produced a series of lenses to facilitate strategic level or curriculum design discussions involving stakeholders across the organisation. You may choose different lenses depending on your role or the stage of curriculum review and design that you are involved with.

Each lens offers a set of related prompts or questions for each of the six ‘beyond blended pillars’. These are not definitive and can be edited to suit your organisational needs. There is some repetition between the lenses as there are some issues that are relevant across all of them. A blank template is also included so you can design a complete lens to suit your project or organisation.

The strategic lenses have been created for those leading curriculum change and those who are designing and implementing it. They highlight specific areas that require a strategic approach to address some of the challenges faced by the HE sector. Each lens provides a series of questions for each of the six pillars.

You can record your own specific strategic organisational questions in the blank template (eg the impact of a new build or refurbishment or expanding course types and student reach).

Curriculum managers/senior managers lens

This lens considers broad questions that link to organisational strategic vision, values and goals. It asks managers to consider how learners and educators currently respond to what is being offered and identify and articulate any problems that need addressing. One example for each pillar is included below:

- Place – what does it mean to be ‘at’ university for our students? How are we building inclusive in-person communities?

- Platform – how are the needs of different programmes and student groups taken into account in the development of platforms and digital infrastructure?

- Pace – what flexibility is afforded for curriculum teams to choose different session types and schedules, including assessment schedules?

- Blend – how are we planning to better integrate online and in place learning experiences?

- Flex – how is resilience being built into the curriculum system to meet future shocks?

- Support – how are we investing in staff/student digital capabilities (for example skills for different modes of learning, teaching and assessment)?

This lens considers broad questions that link to organisational strategic vision, values and goals. It asks managers to consider how learners and educators currently respond to what is being offered and identify and articulate any problems that need addressing. One example for each pillar is included below:

- Place – what does it mean to be ‘at’ university for our students? How are we building inclusive in-person communities?

- Platform – how are the needs of different programmes and student groups taken into account in the development of platforms and digital infrastructure?

- Pace – what flexibility is afforded for curriculum teams to choose different session types and schedules, including assessment schedules?

- Blend – how are we planning to better integrate online and in place learning experiences?

- Flex – how is resilience being built into the curriculum system to meet future shocks?

- Support – how are we investing in staff/student digital capabilities (for example skills for different modes of learning, teaching and assessment)?

Learning space design lens

This lens considers broad questions that link to organisational strategic vision, values and goals around learning spaces. It asks managers to consider how learners and educators currently respond to what is being offered and identify, and to articulate any problems that need addressing. One example for each pillar is included below:

- Place – how does the university estate understand space requirements for different modes of participation? How are these spaces provisioned, in consultation with curriculum teams (for example with recording facilities, plug and play screens, wrap around wifi)?

- Platform – what assumptions are made about learners’ and educators’ access to university platforms? How are these assumptions built into learning space design? How might they evolve in the future, and how might they be different?

- Pace – how are the changing needs of learners taken into account in learning space design (for example consideration of students learning in transit, in parental homes and away from home, in different time zones, and studying while unable to attend in person)?

- Blend – how are IT services supporting diverse learning spaces, with facilities for different modes, alongside relevant safe/durable/accessible devices and systems, and general and specialist software?

- Flex – what spaces, bookable and flexible, are available for students to occupy as they choose? How are students given flexible access to specialist learning spaces such as studios and laboratories?

- Support – do educators have development opportunities (for example formal PG certification, micro credentials, informal workshops and induction sessions) in relation to pedagogic use of learning spaces?

This lens considers broad questions that link to organisational strategic vision, values and goals around learning spaces. It asks managers to consider how learners and educators currently respond to what is being offered and identify, and to articulate any problems that need addressing. One example for each pillar is included below:

- Place – how does the university estate understand space requirements for different modes of participation? How are these spaces provisioned, in consultation with curriculum teams (for example with recording facilities, plug and play screens, wrap around wifi)?

- Platform – what assumptions are made about learners’ and educators’ access to university platforms? How are these assumptions built into learning space design? How might they evolve in the future, and how might they be different?

- Pace – how are the changing needs of learners taken into account in learning space design (for example consideration of students learning in transit, in parental homes and away from home, in different time zones, and studying while unable to attend in person)?

- Blend – how are IT services supporting diverse learning spaces, with facilities for different modes, alongside relevant safe/durable/accessible devices and systems, and general and specialist software?

- Flex – what spaces, bookable and flexible, are available for students to occupy as they choose? How are students given flexible access to specialist learning spaces such as studios and laboratories?

- Support – do educators have development opportunities (for example formal PG certification, micro credentials, informal workshops and induction sessions) in relation to pedagogic use of learning spaces?

Learning platform design and implementation lens

This lens considers broad questions that link to organisational strategic vision, values and goals around learning platforms. It asks managers to consider how learners and educators currently respond to what is being offered and identify and articulate any problems that need addressing. One example for each pillar is included below:

- Place – what assumptions are made about learners’ and educators’ access to platforms from different locations, on and off campus? How are these assumptions informed by evidence?

- Platform – who is involved in the procurement, development and evaluation of learning and teaching platforms (for example IT/digital services, academic teams, students, registry/timetabling, finance, estates, senior management)?

- Pace – how are platforms used to support learning across different times and at different paces (for example providing lecture recordings, offering online collaborative environments, having a range of assignment options, flipped classroom)?

- Blend – how are students supported to engage effectively across a range of platforms, session types and modes of learning?

- Flex – how is information gathered about the platforms students are choosing and the ways they are choosing to engage, and how is this acted upon?

- Support – how are new platforms introduced to educators? What time and support do educators have to understand their affordances for teaching (for example managing presence, managing pace and timing, supporting diverse students, maximising engagement)?

This lens considers broad questions that link to organisational strategic vision, values and goals around learning platforms. It asks managers to consider how learners and educators currently respond to what is being offered and identify and articulate any problems that need addressing. One example for each pillar is included below:

- Place – what assumptions are made about learners’ and educators’ access to platforms from different locations, on and off campus? How are these assumptions informed by evidence?

- Platform – who is involved in the procurement, development and evaluation of learning and teaching platforms (for example IT/digital services, academic teams, students, registry/timetabling, finance, estates, senior management)?

- Pace – how are platforms used to support learning across different times and at different paces (for example providing lecture recordings, offering online collaborative environments, having a range of assignment options, flipped classroom)?

- Blend – how are students supported to engage effectively across a range of platforms, session types and modes of learning?

- Flex – how is information gathered about the platforms students are choosing and the ways they are choosing to engage, and how is this acted upon?

- Support – how are new platforms introduced to educators? What time and support do educators have to understand their affordances for teaching (for example managing presence, managing pace and timing, supporting diverse students, maximising engagement)?

Teaching time and workload lens

This lens considers broad questions that link to organisational strategic vision, values and goals around workload models (WLM) of teaching staff. It asks managers to consider how educators currently respond to the ways they are working and identify and articulate any problems that need addressing. One example for each pillar is included below:

- Place – what flexibility do teaching staff have to decide where they are located when undertaking different aspects of their role?

- Platform – how do WLMs reflect the requirements of different subject areas (for example with online assessments, preparing specialist platforms, software, devices and materials)?

- Pace – how do WLMs recognise the additional time requirements of teaching online (for example facilitation across different time zones, meeting students’ expectations of online support)?

- Blend – do WLMs support the delivery of blended and mixed mode participation (for example is there additional time, allowing for following universal design for learning [UDL] principles and for providing multiple means of engagement in learning)?

- Flex – do WLMs enable educators to respond flexibly to student demand for different session types and modes of learning?

- Support – what rewards and recognition are in place for educators who engage in curriculum and learning design activities, and/or develop their practice to support different modes of participation?

This lens considers broad questions that link to organisational strategic vision, values and goals around workload models (WLM) of teaching staff. It asks managers to consider how educators currently respond to the ways they are working and identify and articulate any problems that need addressing. One example for each pillar is included below:

- Place – what flexibility do teaching staff have to decide where they are located when undertaking different aspects of their role?

- Platform – how do WLMs reflect the requirements of different subject areas (for example with online assessments, preparing specialist platforms, software, devices and materials)?

- Pace – how do WLMs recognise the additional time requirements of teaching online (for example facilitation across different time zones, meeting students’ expectations of online support)?

- Blend – do WLMs support the delivery of blended and mixed mode participation (for example is there additional time, allowing for following universal design for learning [UDL] principles and for providing multiple means of engagement in learning)?

- Flex – do WLMs enable educators to respond flexibly to student demand for different session types and modes of learning?

- Support – what rewards and recognition are in place for educators who engage in curriculum and learning design activities, and/or develop their practice to support different modes of participation?

Equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) lens

This lens considers broad questions that link to organisational strategic vision, values and goals around EDI. It asks managers to consider how educators and learners currently respond to the ways these aspects are being enabled and to identify and articulate any problems that need addressing within the organisation. One example for each pillar is included below:

- Place – how do equality, diversity and inclusion policies and implementation plans address issues of space and place design?

- Platform – how is equitable access to teaching and learning platforms ensured for all learners and educators? Where there are challenges to equitable participation, how are these addressed and mitigated?

- Pace – can learners choose to participate in learning at different times and paces, to suit their different needs?

- Blend – what examples are there of blended curricula meeting a wider range of student needs successfully?

- Flex – what choices do students have around their modes of learning and assessment? Do students understand these choices in relation to their needs, identities and aspirations?

- Support – how does the organisation gather information about different types of diversity, and about how these can be supported through the design of places, platforms, sessions and modes of learning?

This lens considers broad questions that link to organisational strategic vision, values and goals around EDI. It asks managers to consider how educators and learners currently respond to the ways these aspects are being enabled and to identify and articulate any problems that need addressing within the organisation. One example for each pillar is included below:

- Place – how do equality, diversity and inclusion policies and implementation plans address issues of space and place design?

- Platform – how is equitable access to teaching and learning platforms ensured for all learners and educators? Where there are challenges to equitable participation, how are these addressed and mitigated?

- Pace – can learners choose to participate in learning at different times and paces, to suit their different needs?

- Blend – what examples are there of blended curricula meeting a wider range of student needs successfully?

- Flex – what choices do students have around their modes of learning and assessment? Do students understand these choices in relation to their needs, identities and aspirations?

- Support – how does the organisation gather information about different types of diversity, and about how these can be supported through the design of places, platforms, sessions and modes of learning?

Data collection and analytics lens

This lens considers broad questions that link to organisational strategic vision, values and goals around data collection and analytics. It asks managers to consider how this data is used to make decisions about learning, teaching and assessment (LTA). One example for each pillar is included below:

- Place – what data are we collecting on use of buildings and rooms for LTA? How is this associated with particular session types (eg exams, lectures, workshops, practicals)?

- Platform – what data do we collect about how students’ access tools, content and platforms (eg device types, locations, times of day/week)?

- Pace – how do we capture data about the time allocated to different modes, sessions and activities on courses of study?

- Blend – how do we capture data about the modes, sessions and activities planned for each course?

- Flex – how can students and educators control their own data to have more agency in learning and teaching?

- Support – how can we use existing data sets to support curriculum design and delivery better?

This lens considers broad questions that link to organisational strategic vision, values and goals around data collection and analytics. It asks managers to consider how this data is used to make decisions about learning, teaching and assessment (LTA). One example for each pillar is included below:

- Place – what data are we collecting on use of buildings and rooms for LTA? How is this associated with particular session types (eg exams, lectures, workshops, practicals)?

- Platform – what data do we collect about how students’ access tools, content and platforms (eg device types, locations, times of day/week)?

- Pace – how do we capture data about the time allocated to different modes, sessions and activities on courses of study?

- Blend – how do we capture data about the modes, sessions and activities planned for each course?

- Flex – how can students and educators control their own data to have more agency in learning and teaching?

- Support – how can we use existing data sets to support curriculum design and delivery better?

Downloadable resources:

- Beyond blended pillars: strategic lenses prompts and questions (.pdf)

- Beyond blended six pillars strategic lenses presentation (.pptx) or beyond blended six pillars strategic lenses presentation (pdf)

Each lens starts from our ‘beyond blended pillars’ and offers a set of related prompts or questions. These are not definitive and can be edited to suit your organisational needs. There is some repetition between the lenses as there are some issues that are relevant across all of the lenses. A blank template is also included so you can design a complete lens to suit your project or organisation. These lenses have been designed to provide a starting point for strategic discussions around blended learning, such as planning and using campus spaces, timetabling and other related agendas.

Curriculum review and design

Curriculum review is an ongoing process that typically occurs on a cyclical basis, but it can also be triggered by wider organisational factors (eg new builds or refurbishments, new platform procurement and implementation, new strategic goals, expanding into new types of courses) as well as external factors (eg disruptive events like the pandemic, National Student Survey, disruptive technologies such as AI, government interventions, changing student demographics).

Curriculum review can take place at different levels and could involve a range of different stakeholders representing teams with different perspectives. Review processes could take place over a period of time, could involve asynchronous activities as well as in person or online meetings or workshops. A review at strategic level could also feed into reviews at programme or module level, or even trigger them. The materials in this guide can support the different curriculum review processes at both a strategic and a more operational level.

"I’ve taken more than inspiration from the diagram representing the pillars and especially the prompts for curriculum design as a way to help course teams move from the abstract to the concrete, so that they can decide what each of the principles means for them, and define specific actions they can implement to produce the course they want."

Bea de los Arcos, senior learning developer, Extension School for Continuing Education, Delft University of Technology

Learning and teaching strategy review (organisational level)

Strategic review might take place in a range of contexts and be influenced by organisation-wide activities:

- Learning, teaching and assessment strategy development or review

- Organisational portfolio review

- Responding to external factors (eg changes to national frameworks from government or professional/sector bodies)

- Regular internal meetings of senior managers, project boards, teams and inter-professional colleagues

- Specialist meetings for specific projects (eg estates and learning space design, new student records system)

- Stakeholder engagement events or activities (eg students, prospective students, alumni, external partners, local businesses/workplaces)

Resources that can support strategy review

Materials to support strategic conversations and planning:

Materials to support strategic conversations and planning:

Programme design review (faculty/school level)

Programme design review might take place in different contexts and may be influenced by strategic review outcomes:

- Regular or one-off (formal) programme review meetings involving teaching teams, educational developers, IT team/s, learning designers, estates team, students, quality assurance and compliance teams

- Informal curriculum team or teaching team meetings (to inform more formal programme review)

- Internal curriculum design workshops or events mediated by specialists (eg educational developers)

Resources that can support programme design review

Practical resources for adaptation by mediators:

- Six pillars as prompts for curriculum design and strategic thinking (pdf)

- Session types in the four modes of participation - examples (pdf)

- Session types live online mode (.pptx)

- Session types live in place mode (.pptx)

- Session types asynchronous online mode (.pptx)

- Session types asynchronous in place mode (.pptx)

Practical resources for adaptation by mediators:

- Six pillars as prompts for curriculum design and strategic thinking (pdf)

- Session types in the four modes of participation - examples (pdf)

- Session types live online mode (.pptx)

- Session types live in place mode (.pptx)

- Session types asynchronous online mode (.pptx)

- Session types asynchronous in place mode (.pptx)

Module review (school/department level)

Module review may be needed as a result of strategic or programme level review, but may also happen as teaching teams continue to develop and refine their teaching sessions. Changes resulting from module review will ultimately feed back into programme review and some may require consideration at a higher level (eg changes to assessment):

- Teaching team meetings (formal and informal)

- Wider meetings with invited specialists (eg library, educational developers, e-learning team, learning designers)

- Meetings with students (co-design)

Resources that can support module review

Quick reference materials:

- Six pillars as prompts for curriculum design and strategic thinking (pdf)

- Session types in the four modes of participation - examples (pdf)

- Session types live online mode (.pptx)

- Session types live in place mode (.pptx)

- Session types asynchronous online mode (.pptx)

- Session types asynchronous in place mode (.pptx)

Quick reference materials:

- Six pillars as prompts for curriculum design and strategic thinking (pdf)

- Session types in the four modes of participation - examples (pdf)

- Session types live online mode (.pptx)

- Session types live in place mode (.pptx)

- Session types asynchronous online mode (.pptx)

- Session types asynchronous in place mode (.pptx)

Curriculum and learning design process

Curriculum and learning design involve planning and decision making, based on intentional design principles in the context of available information. It leads to outcomes that can be used to communicate and coordinate the curriculum, and shapes learning, teaching and assessment. There are some common processes used across the UK sector in relation to curriculum and learning design. Our research identified that some issues related to curriculum review and design have become more prominent and are prompting the sector to rethink the curriculum design process. These include:

- Ensuring coherence and development pathways in programme-level design

- The rate of change demands more regular review and more in-built flexibility

- A greater variety of courses on offer in terms of time and place creates more complex curriculum designs and portfolio offerings (eg micro, distance)

- The need to represent complex curricula to all involved (eg learner journeys, course maps, flexible models, choice points) and the role of data in this

- Deciding how to engage students in design (complex, time-dependent)

- The impact of organisational agendas on curriculum design (eg EDI, wellbeing, sustainability [use of place and space])

- The need to identify gaps between organisational policies/frameworks and design practices

- A lack of recognition (time, resource, expertise) for curriculum design

- Emerging interest in curriculum analytics – what data in practice is available and is useful, respecting student privacy?

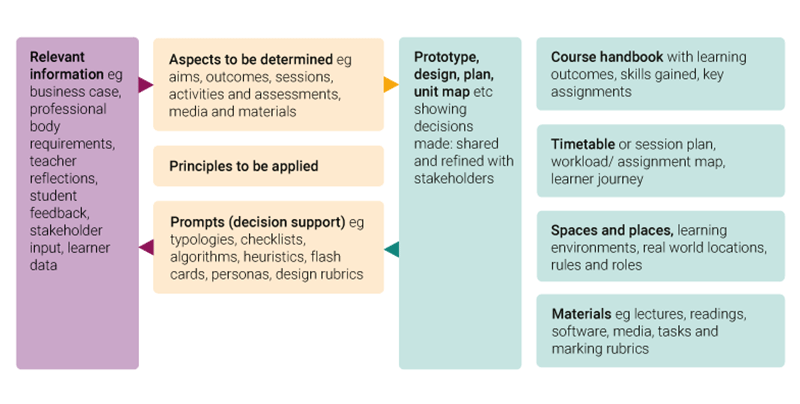

Curriculum and learning design process model

The diagram below illustrates different elements of the design process and how they relate to each other.

Alt text for curriculum and learning design process model diagram

Process model diagram showing different elements of the process and how they relate to each other: key information for design, design process, deliverables

Process model diagram showing different elements of the process and how they relate to each other: key information for design, design process, deliverables

Key information for design (purple section on the process model diagram)

Design is informed by a range of internal organisational factors. It can be constrained by operational aspects such as costing models, staff resources, timetabling, allocation of rooms and other available facilities. Design should also reflect organisational values and principles outlined in strategic documents and consider EDI policies. In addition, designers need to understand features of their typical student cohort, their experiences and expectations around the value of the course (through stakeholder insights, alumni surveys) as well as internal quality frameworks and requirements.

External information should inform the overall rationale articulated in the business case for a course. This can include labour market and competitor intelligence or futures-thinking to identify potential demand, including graduate and employer needs. Design must also meet government standards and benchmarks as well as specific requirements from professional and standards bodies and other wider agendas shaping learning, teaching and assessment.

Key information feeds forward into the design process and is fed back as design is realised in practice as data from systems (eg student achievements and destinations), and qualitative feedback from teaching staff and students.

Key information can shape design in several ways:

- Contact hours, workload models, timetabling, allocation of rooms and facilities all constrain the choice of session types and learning modes

- Student numbers influence choice of session types and group sizes

- Student locations need to be considered (eg transit times and costs, costs of accommodation/heating, visa/border issues)

- Course costs and the need to scale also influence choice of session types, group sizes, platforms and places, types of assessment and feedback

- Standards and benchmarks, depending on subject, may prescribe time (contact hours), skills developed, place (lab, field, placement etc)

- Information about students will influence choice of time, pace and place, activity and interaction: eg access, wellbeing needs, prior study, digital skills

Design process (orange section on the process model diagram)

Curriculum and learning design may take place as a formal meeting, workshop-style session, a design sprint, or over a longer time frame, coordinated by shared documents or a shared design space. It may be carefully structured and facilitated, for example using established external or internal frameworks, or more open-ended. It is important that protected time/space for collaborative working and co-production is provided.

Design involves making decisions about specific aspects of a course, in accordance with (internal and external) principles or standards, and considering the available information. The principles may be broken down and/or made actionable in the form of prompts.

Aspects

The outcome of the design process is usually shaped by the required documentation or a design prototype (eg course map, timeline, pro forma, VLE instance). The prototype dictates the aspects of the course to be determined in the design process. Overall aims and outcomes for the course will be broken down into specific sessions, activities, experiences or learning periods, which shape the requirements for learning platforms and spaces, media and materials.

Principles and prompts

As previously described, the principles to be applied in curriculum design will be informed by internal or externally imposed factors, as well as the specific pedagogic interests and commitments of the course team. Consensus is needed to ensure that these are being realised through the course design.

The following prompts can help to support design across modes of participation:

- How can different modes of participation (in place and online, live and asynchronous) support students to engage?

- What modes best support the subject-specialist practices students undertake?

- Where will students be studying? How will they work together and alone?

- How much time will educators and students spend on different activities?

- What choice and flexibility is really helpful:

- To allow educators to respond to students’ emerging interests and needs?

- To keep each student engaged while keeping the cohort ‘on track’ together?

- To provide pedagogically meaningful alternatives?

Curriculum design workshop or design sprint

Key considerations when running a workshop include:

- Who is involved? What are their roles and responsibilities?

- What organisational processes need to be engaged with?

- How are pedagogic principles expressed in design?

- What information is needed to make good decisions? How are decisions shared and recorded?

- Have we made space to think creatively about course futures?

- How will the outcomes be recorded and communicated? In what different forms?

Deliverables (green section on the process model diagram)

Decisions made in the design workshop are usually shaped by the way deliverables are specified, such as conforming to a particular style of documentation or a design prototype. These deliverables are used to communicate the design, to realise it in practice, to coordinate resources and to provide students with a coherent experience of their course overall.

Key considerations for realising a design in practice include:

- How will the design and associated expectations be communicated?

- How will the design support educators and learners to navigate their roles, tasks and interactions?

- What choices and agency will educators and learners have?

- What opportunities will there be to give and receive feedback?

- Realising a design in practice (example):

- Course handbook – decisions made in the design process are clearly communicated with the teaching staff and students who will realise them in practice

- Timetable – synchronous and asynchronous session types are planned, allocating staff/student time and providing for different kinds of interaction

- Spaces and places – online and real world spaces are made available, affording different interactions (teachers-learners-materials) and activities

- Materials – different media and tools with different functions are provided within sessions and spaces to support learning activities and interactions

Design review (represented by the arrows in the process model diagram)

Part of any curriculum and learning design process is the review and refining stage (indicated by the arrows in the process diagram). It is critical to identify how feedback will be gathered from all stakeholders and how you will respond to this. Capturing the student voice is as important as gathering and analysing data around student outcomes. It is also useful to consider how you might respond to changes in teaching teams or cohort parameters. Many improvements can be made to course design without major revalidation, allowing you to respond to staff or student feedback in a timely way.

Other considerations include the need to choose an effective evaluation framework to enable improvement and how you can respond to changes to learning environments and resources. New online platforms, tools and learning spaces offer potential to offer different modes of participation and possibly changes in teaching and assessment practices.

Downloadable resources:

- Curriculum design process model (.pptx) or Curriculum design process model (pdf)

- Curriculum design process model for curriculum design workshops (.pptx) or Curriculum design process model for curriculum design workshops (pdf)

Our editable slide deck provides options to adapt and use the process model and associated resources in workshops or strategic review settings.

Process review

If your organisation is reviewing its curriculum and learning design process the following questions can prompt some useful discussions:

- How well does the ‘process model’ reflect your experiences and practices?

- Are there things you could be doing differently? Where does resource (time, attention, expertise) need to be added to make things work better?

- If you have an existing framework or design principles, how are they realised in your current design process? How do they work alongside the process model and six pillars?

Our curriculum lenses aimed at practitioners can inform a review of curriculum and learning design.

Curriculum lenses

Our curriculum lenses are aimed at people who are supporting teams as they are redesigning or involved in managing the institution’s learning design support. These are mapped to the six pillars and offer a series of prompts to consider. The prompts can be added to, or edited to suit course issues and organisational approaches to design.

Curriculum design lens

This lens offers broad questions for practitioners around curriculum design, considering the learner and teacher experience. These aim to help identify strengths and challenges, as well as considering the benefits of new and/or different approaches. One example for each pillar is included below:

- Place – where are our students when they are learning outside of timetabled sessions? Do these places provide additional resources eg social, cultural? Do some students need extra support because of their location(s)?

- Platform – how does the curriculum make positive use of online platforms, for example: collaborative writing and design, threaded discussions, diverse media, different ways of interacting?

- Pace – how do we help learners to understand the different demands of live and independent study, and to prepare for them? What support do learners have to engage in different modes (eg provisions for neurodiversity)?

- Blend – how are the resources of time, attention and presence distributed in sessions (sync/async) and in space (place/platform)? Does this distribution reflect the learning experience we want for our students?

- Flex – how do different students prefer to learn, balancing reflective and responsive, self-paced, guided and collaborative modes? How are student differences used as a curriculum resource and a planning guide?

- Support – how does staff continuing professional development/academic development support our teaching in different modes?

This lens offers broad questions for practitioners around curriculum design, considering the learner and teacher experience. These aim to help identify strengths and challenges, as well as considering the benefits of new and/or different approaches. One example for each pillar is included below:

- Place – where are our students when they are learning outside of timetabled sessions? Do these places provide additional resources eg social, cultural? Do some students need extra support because of their location(s)?

- Platform – how does the curriculum make positive use of online platforms, for example: collaborative writing and design, threaded discussions, diverse media, different ways of interacting?

- Pace – how do we help learners to understand the different demands of live and independent study, and to prepare for them? What support do learners have to engage in different modes (eg provisions for neurodiversity)?

- Blend – how are the resources of time, attention and presence distributed in sessions (sync/async) and in space (place/platform)? Does this distribution reflect the learning experience we want for our students?

- Flex – how do different students prefer to learn, balancing reflective and responsive, self-paced, guided and collaborative modes? How are student differences used as a curriculum resource and a planning guide?

- Support – how does staff continuing professional development/academic development support our teaching in different modes?

Assessment and feedback lens

This lens offers broad questions for practitioners around assessment and feedback. They could identify strengths and challenges, as well as helping to consider the benefits of new and/or different approaches. One example for each pillar is included below:

- Place – do our students have access to all the technologies they need in place to complete assignments and assessments?

- Platform – how are we using online assessments creatively to support a diversity of learners and learning, and ensure assessment is authentic to the environments our students are likely to be working in?

- Pace – how can we use differently-paced assessments to support different learners, eg live assessments, time-limited assessments, open-ended assessments, repeat assessments, portfolio assessments?

- Blend – how are assessments distributed through course time to ensure a manageable assessment load (for students) and workload (for educators)?

- Flex – how are the specific purposes of different assessments communicated and discussed with students? What choices do our students have in assessment (eg choice of media, mode, platforms used)?