Exploring the digital pedagogy toolkit

Helping academics to make informed choices when embedding digital into the curriculum.

About the project

The digital pedagogy toolkit has been developed by subject specialists in Jisc’s digital practice team in collaboration with feedback from the UK’s higher, further education and skills sectors.

The key aims of this project include:

- Support academic staff to make informed choices about how they use technology to underpin the curriculum

- Provide ideas and inspiration for how staff can overcome barriers to using technology

- Promote current approaches in curriculum design theory to ensure technology meets the learning outcomes of the course, module or programme of study

- Dispel a range of misconceptions about what can and can’t be achieved by using technology

It is not the intention of this toolkit to provide an overview of a range of digital tools that practitioners can use in a variety of blended learning contexts.

Who is the digital pedagogy toolkit for?

The digital pedagogy toolkit is for professionals who have a role in developing the curriculum. This could include a central group or team that has been tasked with ensuring digital is embedded into programmes of study and will include a range of roles such as teaching staff, librarians, learning technologists and other professional staff.

Although the challenges faced with embedding digital within programmes of study will inevitably vary across sectors and even within institutions, there are nevertheless shared themes. The purpose of the digital pedagogy toolkit is to surface those themes and provide you with ideas for embedding digital wisely whilst underpinning the pedagogy.

It is not the intention of the digital pedagogy toolkit to provide you with a ‘one-size fits all’ solution. Indeed, there isn’t a single approach that guarantees success across such a broad spectrum of contexts, but there are a number of considerations to take into account that will inform your thinking and help you to overcome some of the pitfalls.

We define digital pedagogy as the study of how digital technologies can be used to best effect in teaching and learning.

We define digital pedagogy as the study of how digital technologies can be used to best effect in teaching and learning. ‘Digital technology’ is a broad term and may include both new and emerging technologies as well as more tried and tested technologies.

Top tip

Include short recorded interviews with teachers and learners about their experiences of online learning. This will help to contextualise online for your staff and learners at your institution.

What can you find in the digital pedagogy toolkit?

The digital pedagogy toolkit takes a challenge-based approach by presenting you with a series of scenarios describing areas of digital practice you may want to develop. These scenarios are based in real-world situations that institutions have been grappling with, such as delivering live online learning with students, designing engaging VLE courses or managing digital communities of practice.

This is by no means an exhaustive list of all of the scenarios an institution is likely to encounter when using digital to support the curriculum. As digital evolves, so does our thinking and new ways of utilising digital to best effect will emerge. However, the scenarios included in this toolkit are intended as a starting point to help inform the kinds of considerations to take into account when using digital to support the pedagogy.

Not all of the scenarios will be relevant for all Jisc members. Furthermore, there will undoubtedly be challenges that are specific to your sector and specialism that aren’t represented here.

However, the digital pedagogy toolkit is designed to provide you with a structure for approaching your own challenges to mitigate, where possible, the barriers you face when embedding digital into programmes of study.

Each of the scenarios described in the digital pedagogy toolkit includes the following:

What is the challenge?

A brief description of the challenge, including the sources that have been used to frame this particular challenge.

What questions do you need to ask?

A short section covering the questions to ask before approaching the challenge that will help you determine the best course of action for your context. Links to further resources provide a range of approaches, including case studies, guides and more.

How can digital support the pedagogy?

This is at the heart of the digital pedagogy toolkit and provides an overview of how digital could underpin the pedagogy in the context of the scenario described.

The Education and Training Foundation's (ETF) Digital Teaching Professional Framework (DTPF) includes clear guidance for the FE sector on how teachers can create an effective Hybrid learning environment (Element B5 – Hybrid Teaching).

What are the barriers to meeting this challenge?

The barriers for overcoming many of the challenges relating to digital delivery are often complex and wide-ranging. Training may not always be the answer.

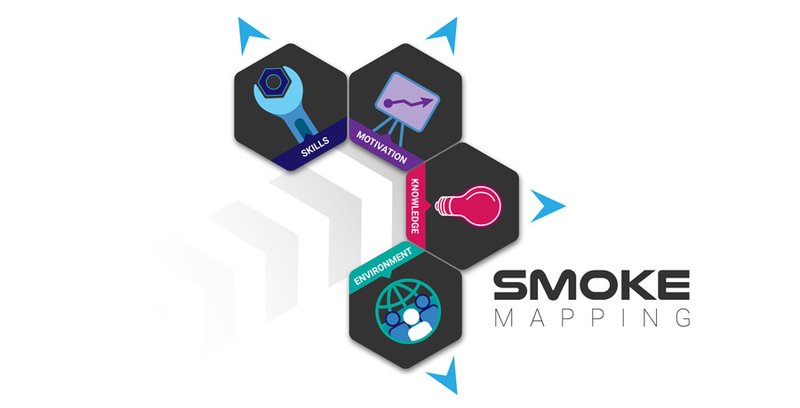

One useful model to apply that looks at the challenge more broadly and helps you to identify the barriers in terms of the skills, motivation, knowledge and environment factors (SMoKE).

Applying the SMoKE model (skills/ motivation/ knowledge/ environment) to the challenge of digital delivery provides a more holistic picture of the barriers that need to be addressed.

What are the myths associated with this challenge?

There are many myths and misconceptions when it comes to using digital. This section exposes the myths and provides suggested approaches for addressing them.

How can the digital pedagogy toolkit be used?

The digital pedagogy toolkit is not designed to be read in a linear fashion, but instead, you are encouraged to dip into sections that interest you. The term ‘toolkit’ has been used figuratively, as the contents are designed to equip you with a range of tools and techniques you can draw on for meeting the specific challenge you face.

We hope this resource will provide a good starting point and possible vehicle for considering which areas of digital practice to review and what questions you may need to ask yourself. However, the contents can also be used by individuals wishing to consider the effectiveness of the measures that they, or the teams they lead, have put into place.

The digital pedagogy toolkit can be used to:

- Explore specific scenarios and consider a range of approaches to address them

- Identify key questions that need to be explored in order to embed digital effectively

- Use as a review tool to reflect on how you plan, design and deliver the digital curriculum

- Signpost further resources to support professional practice

Scenario one: live online learning

This section includes a range of issues to consider that will help you to create an engaging live online learning experience where students will thrive.

What is the challenge?

Delivering live online learning presents a unique set of challenges for both staff and students. Platforms such as Microsoft Teams, Zoom, Google Meet and Adobe Connect all allow tutors to deliver content synchronously to their learners, but what do you need to take into account before delivering live online learning?

This scenario explores how active and collaborative learning as opposed to the more traditional lecture can bring a number of benefits to learning.

What questions do you need to ask?

- What digital competencies and support staff need to be in place to capture, create and broadcast appropriate content and teach effectively using online tools?

- Do staff have access to the tools required to deliver online teaching (eg software, hardware)?

- What guidelines are in place for staff to deliver online in order to encourage best practice (eg use of recorded or live video, etc)?

- Have key policies (safeguarding, teaching, learning and assessment, acceptable use policy, etc) covering the steps you have taken to teach online been updated?

- What measures do you need in place to evaluate the effectiveness of online delivery that involve both staff and students?

- How are learner expectations managed? Are learners provided with guidance on online bullying, privacy and online etiquette?

Find out more

If you want to explore these topics in more detail the following guides and blog posts offer further support:

If you want to explore these topics in more detail the following guides and blog posts offer further support:

How can digital support the pedagogy?

First steps

Before delivering live online learning review your course content to identify which aspects work best in a live session. Much of your course content may work equally well as asynchronous learning objects that learners can access at a time that suits them. This might be background reading prior to the live online session or extension activities following the live session - not everything has to be included in the live session itself.

Live online learning often works best when learners have an opportunity to participate in the session by asking questions, sharing ideas and providing feedback. Timing is key too – checking in with learners at key stages in a course provides them with opportunities to voice any concerns and gives you a valuable temperature check that everyone is on track. Are there any aspects of the course that learners particularly struggle with? Which aspects of the course lend themselves to a live setting where learners can receive instant feedback?

Live online learning often works best when learners have an opportunity to participate in the session

Community of Inquiry model

The Community of Inquiry (CoI) theoretical framework is a model intended to offer ways of learning that are adaptable and encourage collaborative learning, which suits live online sessions perfectly. Although the CoI model has its roots in Lipman’s work from the 90s, the central premise of involving learners and providing meaningful engagement opportunities rather than instruction alone still resonates today. The CoI model encourages teaching practice which facilitates guided inquiry, self-reflection and a shared approach to learning.

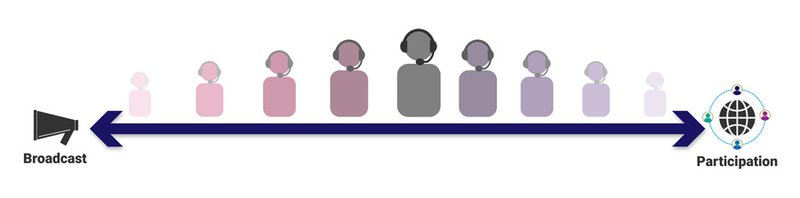

When developing a live online session for learners there will always be a tension between how much tutor-led information and guidance you need to get across and how much time learners can spend collaborating and participating. If the focus is weighted too much towards tutor-led broadcast learners may become distracted and lose interest, whereas too much participation without sufficient guidance may result in misunderstandings. There is always a balance.

Broadcast versus participation

It’s worth reflecting on these two divergent aspects within the context of a live online session. As you move through the session, some components will be more broadcast-based while others will be more participative.

It may be that your learners need far more support and guidance at key stages, edging you closer to the broadcast end of the continuum. Alternatively, the learning activities might favour a more participative approach that calls for greater learner autonomy.

Ask the question - do I have a good range of activities in my session? Are you over-doing the broadcasting where learners are too passive? Have you included timely interactions with learners so they can participate and feel part of the session? Does the balance between these two aspects work?

Tools and techniques

Understanding how to strike the right balance between broadcast and participation is key, but an awareness of what kinds of participation work best and the kinds of activities available on your platforms of choice will also have a bearing. Does your platform support collaborative activities, such as:

- Open mics and breakout rooms for discussion

- Polling and quizzing to check understanding and idea sharing

- Screen sharing and annotation tools to illustrate key concepts

- Recording options to enable learners to re-watch sessions to reinforce understanding

If the platform does, then consider what processes need to be in place for staff to experiment and build confidence with these tools. Providing staff with a critical friend or a safe place to test ideas before they are used with learners can help to reduce anxiety in live online learning sessions.

Many organisations will have an array of supported tools that are available. These can be used safely and securely within the virtual learning environment (VLE) or other organisational platforms. It is a good idea for educators to explore what tools are available from within their organisations first. What elements of the VLE have you not explored? Ask colleagues and learning technologists if there are examples of good practice. Those organisations who have been delivering successful ‘distance learning’ programmes already will have good experiences to share.

Third-party tools

If your platform doesn’t have the functionality you need, there are a range of external tools available that can help boost engagement. There should be a sound reason to use any tool - not just because it is digital. Poor planning of introducing tools could be counter-productive to the learning.

There should be a sound reason to use any tool - not just because it is digital.

The important rule to remember is: what do I want the learner to do? Knowing what you are looking for in a tool can help create a shortlist rather than searching without a proper aim. It is also important to find a tool that is a good fit for the job you are looking to fulfil. Be wary of changing the learning to fit around a tool!

Establishing boundaries online

A move to live online delivery may make many teachers anxious about how to model appropriate online behaviour and protocols with learners. Meeting with students online may cause concerns about breaching boundaries or questions about etiquette. It’s important to ensure that both staff and students are protected and understand how to maintain boundaries online.

In addition to revising the key policies discussed previously, staff may also find the following tips useful:

- Clearly communicate your expectations to students when working online. Guidance may be as simple as reminding students to dress as they would in class when using webcams

- Recording online sessions not only creates a useful reference for students, you will also have a record of exactly what was said. Be mindful that even if you do not record a session, a student might, so do not say anything that you would not be comfortable with becoming public

- Using a webcam can add a personal touch and help to build rapport, but be mindful of your surroundings and, if possible, use a dedicated workspace. When presenting online, consider the impacts of having your webcam on for yourself and your learners as outlined in the table below. Guidance on the pros and cons of each approach is also available in our blog post

Considerations for having cameras on

- Can help to make learners feel more connected, especially in small groups

- Having the presenter camera on at the start of a session helps to personalise the session

- Can humanise the presenter/learners and help with relationship building

- Easier to convey body language to help with understanding

- Can help to make learners feel more connected, especially in small groups

- Having the presenter camera on at the start of a session helps to personalise the session

- Can humanise the presenter/learners and help with relationship building

- Easier to convey body language to help with understanding

Considerations for having cameras off

- Less strain on the bandwidth, which may be an issue for many staff/learners on a poor connection

- Some learners may feel vulnerable or exposed

- Removes staff and learner privacy issues if they are working from home

- If presenting and sharing screen or content having cameras on can clutter the screen estate and cause distractions

- Less strain on the bandwidth, which may be an issue for many staff/learners on a poor connection

- Some learners may feel vulnerable or exposed

- Removes staff and learner privacy issues if they are working from home

- If presenting and sharing screen or content having cameras on can clutter the screen estate and cause distractions

Top tip

Colleagues across the FE sector have shared a range of tips via short videos that highlight good practice in the area of remote teaching.

What are the barriers to meeting this challenge?

What are the skills factors?

Can staff meet (are they aware of) accessibility standards?

Making digital content fully accessible can help improve student engagement with learning and improve outcomes.

Accessibility of your digital estate is not only a legal requirement. Content that meets high standards of accessibility is more user-friendly, understandable, and robust in that it will display well across different browsers and devices.

Read our guide on what steps you can take to meet accessibility regulations.

Making digital content fully accessible can help improve student engagement with learning and improve outcomes.

Accessibility of your digital estate is not only a legal requirement. Content that meets high standards of accessibility is more user-friendly, understandable, and robust in that it will display well across different browsers and devices.

Read our guide on what steps you can take to meet accessibility regulations.

Baseline staff capabability

Do staff have a baseline of digital tools and techniques necessary to deliver active learning?

Do staff have a baseline of digital tools and techniques necessary to deliver active learning?

What are the motivation factors?

Supporting reluctant staff

Delivering live online learning may push digitally-shy staff out of their comfort zone, making them reluctant to take part.

Consider how good practice in live online delivery is shared and celebrated across the institution to help build confidence and participation.

Delivering live online learning may push digitally-shy staff out of their comfort zone, making them reluctant to take part.

Consider how good practice in live online delivery is shared and celebrated across the institution to help build confidence and participation.

Ensuring staff wellbeing

Teaching staff may struggle to switch off if clear boundaries are not established from the offset around which platforms will be used for which purpose.

Identify which aspects of a course work best as a live online session (such as tutorials, Q&A drop-ins, etc) and which work best as asynchronous activities – not every aspect of a course needs to be replicated live online. It’s important for staff digital wellbeing that they can detach themselves from work and have the downtime they need.

Teaching staff may struggle to switch off if clear boundaries are not established from the offset around which platforms will be used for which purpose.

Identify which aspects of a course work best as a live online session (such as tutorials, Q&A drop-ins, etc) and which work best as asynchronous activities – not every aspect of a course needs to be replicated live online. It’s important for staff digital wellbeing that they can detach themselves from work and have the downtime they need.

What are the knowledge factors?

Are staff aware of what good live online learning looks like?

Staff need an understanding of what good live online learning looks like and guidance on how to work towards it.

The Open University Learning Design team have created an infographic for staff outlining ten uses for live online learning spaces to inspire and help staff.

Staff need an understanding of what good live online learning looks like and guidance on how to work towards it.

The Open University Learning Design team have created an infographic for staff outlining ten uses for live online learning spaces to inspire and help staff.

Staff induction

Is staff induction carried out using organisational platforms, tools and techniques demonstrating good practice? Do staff know how others are using online sessions?

Another approach would be to incorporate good practice into any induction programme for new staff and build this into CPD channels.

Is staff induction carried out using organisational platforms, tools and techniques demonstrating good practice? Do staff know how others are using online sessions?

Another approach would be to incorporate good practice into any induction programme for new staff and build this into CPD channels.

What are the environmental factors?

Access to platforms, equipment and software

Do staff have access to platforms with the appropriate functionality to deliver live online learning?

Once these systems have been identified it is worth checking that all staff have the equipment and software required, such as mics and/or headsets, webcams, and sufficient licences for accessing any specialist software.

Do staff have access to platforms with the appropriate functionality to deliver live online learning?

Once these systems have been identified it is worth checking that all staff have the equipment and software required, such as mics and/or headsets, webcams, and sufficient licences for accessing any specialist software.

Guidance and support processes

Guidance and support processes are in place to enable staff to use them to a base level of effectiveness.

Guidance and support processes are in place to enable staff to use them to a base level of effectiveness.

Policy

Relevant policies have been revised and communicated to both staff and learners.

Relevant policies have been revised and communicated to both staff and learners.

What are the myths associated with this challenge?

Top tip

Coleg y Cymoedd gather feedback from learners (via academic board, learner voice forums, etc) about controversial issues on what their experiences of online learning are like. This dispels some of the misconceptions about what impacts technology has on learning.

A number of apocryphal stories surround live online learning, which can often have an unhelpful impact on staff when approaching the topic. Some of these myths are more common than others, but many of them are likely to surface in your conversations with peers when discussing live online learning.

The following myths are worth reflecting on with colleagues and include strategies that you can adopt to mitigate them.

Myth: delivering online learning involves the latest digital technologies

The allure of shiny new technology is seductive. It’s tempting to think that if we adopt cutting-edge technologies then these things will automatically transform our practice. However, the issue is that using innovative technology doesn’t inevitably make us more innovative. It’s entirely possible to transform practice using the simplest of digital tools.

It’s often better to start with more tried and tested platforms that both staff and students already have a degree of familiarity with. Many staff may feel left behind and lack confidence with technology. It’s important to ensure staff are provided with opportunities to share knowledge, practices and experiences with colleagues.

The allure of shiny new technology is seductive. It’s tempting to think that if we adopt cutting-edge technologies then these things will automatically transform our practice. However, the issue is that using innovative technology doesn’t inevitably make us more innovative. It’s entirely possible to transform practice using the simplest of digital tools.

It’s often better to start with more tried and tested platforms that both staff and students already have a degree of familiarity with. Many staff may feel left behind and lack confidence with technology. It’s important to ensure staff are provided with opportunities to share knowledge, practices and experiences with colleagues.

Myth: online environments are usually “safe spaces”

Where someone who is from a socially privileged background may be able to interact freely, other individuals or groups of individuals may be disadvantaged or more at risk in these spaces. Make sure there are effective mechanisms in place to capture students’ experience of live online learning, so any concerns or barriers from disadvantaged groups can be addressed.

Where someone who is from a socially privileged background may be able to interact freely, other individuals or groups of individuals may be disadvantaged or more at risk in these spaces. Make sure there are effective mechanisms in place to capture students’ experience of live online learning, so any concerns or barriers from disadvantaged groups can be addressed.

Myth: the students all use social media so it makes sense to use that

Using popular social media tools may well be simple to use with learners, but the risk of your work life bleeding into your personal life is higher. Boundaries between personal and professional can easily blur on social media.

The move to online relationships with staff and students could affect the assessment of risk or the effectiveness of existing measures. Make sure code of conduct and acceptable use policies are revised accordingly, so staff and student expectations are clear.

Using popular social media tools may well be simple to use with learners, but the risk of your work life bleeding into your personal life is higher. Boundaries between personal and professional can easily blur on social media.

The move to online relationships with staff and students could affect the assessment of risk or the effectiveness of existing measures. Make sure code of conduct and acceptable use policies are revised accordingly, so staff and student expectations are clear.

Scenario two: what makes an engaging course on the virtual learning environment (VLE)?

Here we will look at some key issues you need to consider, to ensure students engage with your VLE courses.

What is the challenge?

Simply moving existing learning content to online platforms for students to consume is not the same as having an engaging course.

Although students do benefit from access to materials such as slide decks, lecture notes and content capture, these alone can make for a passive experience.

Not all institutions use the same platform for a VLE. Some intentionally (or unintentionally) have multiple platforms fulfilling the role.

During the Covid lockdown many staff had to use a different platform to their VLE to maintain teaching, learning and assessment. As teaching returned to campus spaces, some staff continued to use those new platforms instead of returning to the VLE.

Whichever platform(s) the organisation uses, it is important to ensure a consistent experience. This includes consistency with the page layout, the tools employed and even the platform itself.

What questions do you need to ask?

There are a number of considerations to reflect on when addressing the challenge of designing an engaging course on the VLE:

What staff development opportunities are available to support you?

Consider what channels are available to support staff to develop their own digital practice and build their confidence to explore and experiment in new ways of delivery. This could range from bespoke staff development sessions to online bitesize video tutorials demonstrating specific functions of the VLE.

Does the institution have guidance on the use of VLE?

Every user of the VLE needs to have an understanding of the role of the platform to gain the best experience. A lack of understanding can affect the practices and motivation of the people using it. This can lead to inconsistencies in layout, tools and experience. Templates and best practices are easy to communicate, but ensuring people understand why it is important to maintain a consistent experience can provide a more effective platform.

Does the institution have a policy on the use of technologies?

Check your institution’s guidance on which technologies are supported and deemed safe. You may find specific technologies are not supported and any which are subject to GDPR restrictions.

How can you include students to make a more engaging course on the VLE?

Building in opportunities for students to engage with your VLE course makes it more likely that the VLE will be used effectively. Consider how the tools available within the VLE align with the overall learning objectives for the course. Technology provides many new opportunities to re-evaluate how are you interact with your students.

Find out more

If you want to explore these topics in more detail the following guides and blog posts offer further support:

If you want to explore these topics in more detail the following guides and blog posts offer further support:

How can digital support the pedagogy?

Delivering learning in online contexts requires an adjustment in thinking and the time students spend learning online needs to be structured differently from face-to-face sessions. For example, what might make up a two-hour lecture could be split up into different sections with activities throughout the day, or even week, in an online VLE course. Digital technology allows us to rethink the traditional lecture mindset and design learning in such a way that is more flexible and manageable for learners to access.

Many students accessing online content on your VLE may struggle with online learning and need further support. For some students this may be bandwidth issues or inadequate home study spaces to work effectively; others may find remote working a strain when they are distanced from their peers and support network. Student Minds, the UK’s leading mental health charity, have developed the Student Space site which provides tips and support to help students feel more confident about working online.

Being mindful of the challenges students face with remote working helps when planning your VLE course.

Being mindful of the challenges students face with remote working helps when planning your VLE course. For example, providing students with a range of both synchronous and asynchronous activities allows students to study flexibly whilst still feeling connected with their tutors and peers.

Top tip

Wrexham Glyndwr University have a dedicated area of support materials on the platform that staff will be using to create learning activities with their own students.

Synchronous learning

Synchronous sessions provide opportunities for consolidation of learning through live activities, such as learner presentations, discussion, learner pair and group work, learner self-assessment and tutor feedback.

They can be an invaluable and engaging way of keeping learners connected with their peers and tutor, but do need to be timetabled and require learners to be available at set times with good connectivity.

Asynchronous learning

Asynchronous sessions provide opportunities for learners to consolidate their learning through a range of means; for example, independent study through videos, podcasts, course work, shared documents, assignments and assessment. Although students can complete these at a time that suits they still need staff to provide guidance on what they need to complete and in by what timeframes.

The description of the work may be usefully ‘chunked’ providing the learner with an initial idea of the learning objectives they should achieve by the end of the section and engage the learners in activities, such as reading, researching, organising their learning and views, writing assignments.

Top tip

The University of the Highlands and Islands provide academic staff with a set of recommended activities that they can embed into their online courses, including:

- FAQ section for students to raise any questions or concerns

- A social announcements discussions board so students could organise their own study spaces with peers outside of the institutional platforms if they wanted.

- A virtual office hours drop-in sessions for students to have live conversations with their tutors.

This provides staff with a good starting point and ensures that learners feel connected to their tutors and peers. Staff were also provided with placeholder text for all of these activities which they could adapt to suit their students’ needs. Further recommendations relating to achieving the right mix of synchronous and asynchronous activities is also available for academic staff can be found on the university's website.

Learning design

Do staff have access to tools and frameworks to assist with blended learning curriculum design?

Many institutions have developed a specific learning design process and encourage its use when designing modules and programmes of study on the VLE. One of the most widely known is Gilly Salmon’s Carpe Diem, a team-based approach to learning design that brings together course teams, learning technologists, subject librarians and even employers. Other flavours of Carpe Diem have also been developed, such as UCL’s collaborative ABC toolkit for blended learning curriculum redesign (see the video below).

Adopting a collaborative approach to the learning design process across the institution taps into expertise across departments and ensures a degree of consistency within VLE courses.

What are the barriers to meeting this challenge?

What are the skills factors?

Can staff meet (are they aware of) accessibility standards?

Making digital content fully accessible can help improve student engagement with learning and improve outcomes.

The Further and Higher Education Digital Accessibility Working Group has prepared a digital accessibility toolkit that contains sector-sourced guidance.

Making digital content fully accessible can help improve student engagement with learning and improve outcomes.

The Further and Higher Education Digital Accessibility Working Group has prepared a digital accessibility toolkit that contains sector-sourced guidance.

Baseline staff capability

Do staff have a baseline of digital tools and techniques necessary to deliver active learning?

Do staff have a baseline of digital tools and techniques necessary to deliver active learning?

What are the motivation factors?

Supporting reluctant staff

Delivering live online learning may push digitally-shy staff out of their comfort zone, making them reluctant to take part.

Consider how good practice in live online delivery is shared and celebrated across the institution to help build confidence and participation.

Delivering live online learning may push digitally-shy staff out of their comfort zone, making them reluctant to take part.

Consider how good practice in live online delivery is shared and celebrated across the institution to help build confidence and participation.

Ensuring staff buy-in

The technology is not always the primary barrier to introducing new ways of working for some staff, it can also be about people and culture change.

For a successful outcome, students and staff need to feel supported and given due recognition in their use of technology.

The technology is not always the primary barrier to introducing new ways of working for some staff, it can also be about people and culture change.

For a successful outcome, students and staff need to feel supported and given due recognition in their use of technology.

What are the knowledge factors?

Are staff aware of what a good VLE course looks like?

Staff need an understanding of what a good VLE course looks like and guidance on how to work towards it.

They can often lack understanding of the potential of the VLE to enable them to go beyond a ‘repository model' approach. They need to be able to experience what “good” looks like and explore new ways of teaching, in a safe space, to build confidence.

Staff need an understanding of what a good VLE course looks like and guidance on how to work towards it.

They can often lack understanding of the potential of the VLE to enable them to go beyond a ‘repository model' approach. They need to be able to experience what “good” looks like and explore new ways of teaching, in a safe space, to build confidence.

Staff induction

Is staff induction carried out using organisational platforms, tools and techniques demonstrating good practice? Do staff know how others are designing VLE courses?

Another approach would be to incorporate good practice into any induction programme for new staff and build this into CPD channels.

Is staff induction carried out using organisational platforms, tools and techniques demonstrating good practice? Do staff know how others are designing VLE courses?

Another approach would be to incorporate good practice into any induction programme for new staff and build this into CPD channels.

What are the environmental factors?

Strategy

Is there an agreed role and clear direction for the development of the VLE and how is this communicated to staff?

Having a strategic approach in place that encourages collaboration helps to mitigate barriers, such as accessibility issues for students and join-up with digital resources available from the library.

Is there an agreed role and clear direction for the development of the VLE and how is this communicated to staff?

Having a strategic approach in place that encourages collaboration helps to mitigate barriers, such as accessibility issues for students and join-up with digital resources available from the library.

Access to platforms, equipment and software

Do staff have access to the appropriate functionality to design an engaging VLE course?

Once these systems have been identified it is worth checking that all staff have the equipment and software required, such as mics and/or headsets, webcams, and sufficient licences for accessing any specialist software.

Do staff have access to the appropriate functionality to design an engaging VLE course?

Once these systems have been identified it is worth checking that all staff have the equipment and software required, such as mics and/or headsets, webcams, and sufficient licences for accessing any specialist software.

What are the myths associated with this challenge?

A number of myths surround the VLE, which can often have an unhelpful impact on staff when approaching the topic. Some of these myths are more common than others, but many of them are likely to surface in your conversations with peers.

The following myths are worth reflecting on with colleagues and include strategies that you can adopt to mitigate them.

Myth: if I put teaching content on the VLE, students won’t turn up for live sessions

Materials on the VLE can complement live sessions by providing opportunities to:

- Prepare for live sessions

- A chance to catch up if the student is unable to attend live

- Needs more time to explore a topic

- Opportunity for revision

With some of the content available asynchronously rather than live, the teacher can devote more time in the live session to active learning experiences and interaction with and between students.

Materials on the VLE can complement live sessions by providing opportunities to:

- Prepare for live sessions

- A chance to catch up if the student is unable to attend live

- Needs more time to explore a topic

- Opportunity for revision

With some of the content available asynchronously rather than live, the teacher can devote more time in the live session to active learning experiences and interaction with and between students.

Myth: all digital content may be shared freely for teaching purposes

Unfortunately this is not the case. UK copyright law was last changed in 2014, bringing in a number of new or updated exceptions intended to support teaching in digital contexts. Government guidance on copyright exceptions relating to teaching states:

“the copying of works in any medium as long as the use is solely to illustrate a point, it is not done for commercial purposes, it is accompanied by a sufficient acknowledgement, and the use is fair dealing. This means minor uses, such as displaying a few lines of poetry on an interactive whiteboard, are permitted, but uses which would undermine sales of teaching materials are not.”

However, this does require a certain degree of what Secker and Morrison (2020) call “copyright literacy” on behalf of the user and it is unlikely that you can teach online without having to deal with matters of copyright. If you are unsure, check with the copyright specialist in your university or college for a second opinion.

Unfortunately this is not the case. UK copyright law was last changed in 2014, bringing in a number of new or updated exceptions intended to support teaching in digital contexts. Government guidance on copyright exceptions relating to teaching states:

“the copying of works in any medium as long as the use is solely to illustrate a point, it is not done for commercial purposes, it is accompanied by a sufficient acknowledgement, and the use is fair dealing. This means minor uses, such as displaying a few lines of poetry on an interactive whiteboard, are permitted, but uses which would undermine sales of teaching materials are not.”

However, this does require a certain degree of what Secker and Morrison (2020) call “copyright literacy” on behalf of the user and it is unlikely that you can teach online without having to deal with matters of copyright. If you are unsure, check with the copyright specialist in your university or college for a second opinion.

Myth: the students all use social media so it makes sense to use that

Using popular social media tools may well be simple to use with learners, but the risk of your work life bleeding into your personal life is higher. Boundaries between personal and professional can easily blur on social media.

The move to online relationships with staff and students could affect the assessment of risk or the effectiveness of existing measures. Make sure code of conduct and acceptable use policies are revised accordingly, so staff and student expectations are clear.

Using popular social media tools may well be simple to use with learners, but the risk of your work life bleeding into your personal life is higher. Boundaries between personal and professional can easily blur on social media.

The move to online relationships with staff and students could affect the assessment of risk or the effectiveness of existing measures. Make sure code of conduct and acceptable use policies are revised accordingly, so staff and student expectations are clear.

Scenario three: managing digital communities of learning

How can we build and manage digital communities of learning that foster a sense of belonging and encourage collaboration?

What is the challenge?

Whatever form teaching takes in future it is highly likely to involve an element of online or hybrid. Access to digital content and services is important, but a greater concern is how we can create a sense of community and collaboration when students are learning online.

Much of the value that students perceive in going to university or college comes from interaction and relationships.

Many of the approaches and skills in managing the social aspects of learning in traditional settings carry over into online environments, but supporting online communities of learners brings with it new opportunities as well as challenges.

Top tip

Develop a buddy or mentoring system for academic staff so they don’t feel isolated using technology and have a critical friend to offer feedback and support.

What questions do you need to ask?

How do I keep learners safe?

As with learning in the physical environment, institutions have a fundamental duty of care to students in online spaces. The risks are different but no less serious and learners are much less likely to engage if they don’t feel adequately protected. This is why Jisc published this guide on supporting online safety.

It’s worth remembering that online spaces may not universally be perceived as safe, even when hosted on an institution’s systems. For some marginalised individuals and social groups, engaging in online spaces can make them feel vulnerable. That vulnerability may also extend outside the online community; a feeling of threat in an online forum may lead to a feeling of threat in the physical world.

How do I encourage engagement?

Avoid the assumption that students will automatically be active in an online community or know what to do. The idea that “digital natives” using technology fluently and instinctively has been shown to be an unhelpful analogy.

Avoid the assumption that students will automatically be active in an online community or know what to do.

Gradually induct students into participation. Don’t throw students in at the deep end and expect them to swim like porpoises. For example, use Gilly Salmon’s 5 stage model to scaffold the student experience.

The premise of Salmon’s model is that in order to facilitate higher levels of learning and social participation, we first need to make sure:

- Do students have enough information and resources to be able to connect and participate? This will vary from student to student and some may have particular needs to allow them to participate on an equal footing with others.

- Have they been welcomed into the space?

- Are they able to exchange messages and build connections with you as the teacher as well as each other?

Without those in place, the likelihood of some students becoming disengaged and potentially dropping out increases.

As with learning in the physical world, without specific action, the majority of activity in online spaces tends to come from a subsection of the community, often a minority. Efforts to reach out and actively involve larger proportions of an online community can take effort on the part of teaching staff or tutors which should be acknowledged by the organisation and incorporated into planning and resourcing to ensure the quality of online learning.

Give learners a reason to participate. Incorporate community activities and peer to peer marking and feedback into the curriculum. Collaborative activities and project-based learning can be managed very effectively in online social spaces. A content-based curriculum which focuses on transmission of information will create fewer reasons for people to engage socially.

Conversation or broadcast

Look closely at how you interact with the community. What language are you using? Sometimes it’s important to broadcast information but if that is all you are doing, learners will lack an explicit reason to respond or take part in a conversation. See the section on broadcast versus participation to get a flavour of the balance needed.

Use more questioning. Perhaps be less definitive or comprehensive in the information you give and leave more room for debate, analysis and questioning where appropriate.

Have a look at this research poster by Chua Shi Min which analyses conversation in online learning communities and makes suggestions about making language choices that encourage people to reply to messages and not just passively consume them.

Look closely at how you interact with the community. What language are you using? Sometimes it’s important to broadcast information but if that is all you are doing, learners will lack an explicit reason to respond or take part in a conversation. See the section on broadcast versus participation to get a flavour of the balance needed.

Use more questioning. Perhaps be less definitive or comprehensive in the information you give and leave more room for debate, analysis and questioning where appropriate.

Have a look at this research poster by Chua Shi Min which analyses conversation in online learning communities and makes suggestions about making language choices that encourage people to reply to messages and not just passively consume them.

Offering support

This can be a challenge, particularly with larger groups of students.

Be clear about the best methods of contacting you or the teaching team and the timescales for expecting a response.

Consider having open channels for people asking for help where the learner community can start to build a “knowledge-base”, or a collaborative document that answers common queries. This might help take the pressure off you as an individual and give the community another reason to exist.

Also, provide private channels where learners can communicate with you in confidence.

This can be a challenge, particularly with larger groups of students.

Be clear about the best methods of contacting you or the teaching team and the timescales for expecting a response.

Consider having open channels for people asking for help where the learner community can start to build a “knowledge-base”, or a collaborative document that answers common queries. This might help take the pressure off you as an individual and give the community another reason to exist.

Also, provide private channels where learners can communicate with you in confidence.

Be a community

Communities are made up of different, identifiable individuals, taking on different roles both formally and informally and this is something to encourage. If you had to picture the flow of energy in the community does it flow from you as a teacher towards the students, or is it something much more diffuse? The former will be exhausting for you and give your learners less reason to engage. The latter is a sign of a healthier community with a flatter structure.

Think about how you could make your community more of a partnership between teacher and learners. Allow learners to share their experiences and to play a role in shaping how learning happens. And model community-minded behaviour to them.

Communities are made up of different, identifiable individuals, taking on different roles both formally and informally and this is something to encourage. If you had to picture the flow of energy in the community does it flow from you as a teacher towards the students, or is it something much more diffuse? The former will be exhausting for you and give your learners less reason to engage. The latter is a sign of a healthier community with a flatter structure.

Think about how you could make your community more of a partnership between teacher and learners. Allow learners to share their experiences and to play a role in shaping how learning happens. And model community-minded behaviour to them.

Remember that “engagement” in an online environment might look very different. Students may prefer to listen and observe goings-on rather than participate actively, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they are disengaged.

How can digital support the pedagogy?

Communities of Inquiry

Communities of Inquiry or CoI give us a way of looking at how a community of students and teachers engage in authentic inquiry.

Cleveland-Innes, Garrison and Vaughan at Athabasca University in Canada have created a web resource that looks at the constituent parts of the CoI model and relates it to online educational experiences.

A key message about CoI is that the idea of “presence” is a complex one.

Measuring effectiveness

How you use data can have an impact on pedagogical issues but the relationship is complex.

Online community spaces often allow detailed analysis on user activity. Where this data can be useful it can give a narrow interpretation of what activity is happening. What we want to achieve for learners is engagement but the things that are commonly easily measured in online spaces could be better described as “attention”. Attention isn’t always a good proxy measure for engagement as this post argues.

Analytics can give you useful information about some aspects of how people are engaging with the platform.

Analytics can give you useful information about some aspects of how people are engaging with the platform. For example, you might be able to see that most activity happens within the community on a particular day or between particular times. This could inform when you make yourself available for live support chats or group discussions. Looking at how active certain people are in the community might give you clues as to who to have conversations with to check progress, looking for early warning signs of difficulties.

Organisations should also consider the impact of data collection might have on learning and social behaviours. It pays to be open and transparent with students about what data is being collected and how it is being used. Jisc has produced a code of practice for learning analytics that is relevant here.

Analysis of data needs to go hand-in-hand with more conversational approaches to determine levels of engagement.

Remember that “engagement” in an online environment might look very different. Students may prefer to listen and observe goings-on rather than participate actively, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they are disengaged.

What are the barriers to meeting this challenge?

What are the skills factors?

Collaborative learning

How able are your students to work collaboratively? Can students create and share documents online for collaboration, reading and review? Are students able to demonstrate positive and constructive behaviours in the community?

How able are your students to work collaboratively? Can students create and share documents online for collaboration, reading and review? Are students able to demonstrate positive and constructive behaviours in the community?

What are the motivation factors?

Online safety

Are students telling you that they feel safe in the online space?

Are students telling you that they feel safe in the online space?

Student employability

Are students able to associate their participation with developing skills that will make them more employable?

Are students able to associate their participation with developing skills that will make them more employable?

Staff as role models

Do students see teaching staff modelling good community-minded practice?

Do students see teaching staff modelling good community-minded practice?

What are the knowledge factors?

Understanding what is possible

Do you and your students know the features of the online platforms you are using and the tools that are available?

Do you and your students know the features of the online platforms you are using and the tools that are available?

Online identity and data security

Do students know how to create online profiles and manage their online identity using security and privacy settings? Do students know how to keep their own and other people’s data secure?

Do students know how to create online profiles and manage their online identity using security and privacy settings? Do students know how to keep their own and other people’s data secure?

Learner expectation and concerns

Are students aware of the types of behaviour expected of them? Do your learners know how to raise concerns about their studies or about interactions with other students?

Are students aware of the types of behaviour expected of them? Do your learners know how to raise concerns about their studies or about interactions with other students?

What are the environmental factors?

Equipment

Do students have the right equipment and sufficient, reliable connectivity to participate?

Do students have the right equipment and sufficient, reliable connectivity to participate?

Study spaces

Do they have access to physical space to study and participate? Participation might involve voice calls so can they do this easily living in shared accommodation or while caring for family?

Do they have access to physical space to study and participate? Participation might involve voice calls so can they do this easily living in shared accommodation or while caring for family?

Accessibility

Are online learning spaces, activities and resources truly accessible to all learners by default?

Are online learning spaces, activities and resources truly accessible to all learners by default?

Online safety

Are you and your students aware of how to report safety, privacy or security concerns? Are there policies in place that are up to date and fit for purpose?

Are you and your students aware of how to report safety, privacy or security concerns? Are there policies in place that are up to date and fit for purpose?

What are the myths associated with this challenge?

A number of myths surround digital communities of learning, which can often have an unhelpful impact on staff when approaching the topic. Some of these myths are more common than others, but many of them are likely to surface in your conversations with peers.

The following myths are worth reflecting on with colleagues and include strategies that you can adopt to mitigate them.

Myth: young people are “digital natives” and will just “get” how to be part of a learning community online

The critique of Prensky’s Native and Immigrants model is detailed but simply, a familiarity with certain types of technologies in certain contexts does not necessarily translate into using technology to support learning. Age is not the prime determiner.

The critique of Prensky’s Native and Immigrants model is detailed but simply, a familiarity with certain types of technologies in certain contexts does not necessarily translate into using technology to support learning. Age is not the prime determiner.

Myth: analytics will tell you about engagement when what they’re actually measuring is attention

Engagement is a complex thing to define and is often done on the learner’s terms, not the teacher or organisation.

Attention stats like clicks, site visits, assessment scores collectively may build a detailed picture of activity but it’s difficult to make these into a direct proxy for engagement with learning.

Engagement is a complex thing to define and is often done on the learner’s terms, not the teacher or organisation.

Attention stats like clicks, site visits, assessment scores collectively may build a detailed picture of activity but it’s difficult to make these into a direct proxy for engagement with learning.

Myth: online environments are uniformly “safe spaces”

Where someone who is from a socially privileged background may be able to interact freely, other individuals or groups of individuals may be disadvantaged or more at risk in these spaces.

Where someone who is from a socially privileged background may be able to interact freely, other individuals or groups of individuals may be disadvantaged or more at risk in these spaces.

Scenario four: effective hybrid learning

A positive student experience for students studying both remotely and in person.

What is the challenge?

Teaching some students in person whilst others attend remotely presents a number of challenges for teaching staff. Although this can provide students with a degree of choice in how they experience their learning, it also raises questions about parity and quality of experience.

With many courses being designed to accommodate a hybrid delivery style let’s take a rounded view of how our colleges and universities are approaching this. What measures can institutions put in place to ensure that students studying both remotely and in person receive a positive student experience?

What questions do you need to ask?

There are a number of considerations to reflect on when addressing the challenge of providing an effective hybrid learning environment, such as:

- Consider which courses already have aspects delivered remotely and identify tried and tested methods that are scalable across other courses (for example, recordings, captioned video, lecture capture).

- What digital competencies and support need to be in place to capture, create and broadcast appropriate content to teach effectively using digital tools?

- Do staff have access to the tools required to deliver hybrid teaching (eg software, hardware)? Students attending in person at a university or college often have access to specialised software and staff that may be difficult to replicate when learning remotely.

- What guidelines are in place for staff to deliver in hybrid contexts to encourage best practice (eg use of recorded or live video, etc)?

- Have you updated key policies (safeguarding, teaching, learning and assessment, acceptable use policy, etc) covering the steps you have taken to teach in hybrid contexts?

- What measures do you need in place to evaluate the effectiveness of hybrid delivery that involve both staff and students?

- How are learner expectations managed? Are learners provided with guidance on online bullying, privacy and online etiquette?

- What digital learning resources and library support are in place? These benefit both in person and online learners. Talk to your library/learning resources staff to find out how they can help you and your learners.

Watch learners from Coleg Sir Gar share their views of hybrid, both good and bad experiences.

How can digital support the pedagogy?

Considering hybrid on a course-by-course basis

Universities and colleges offer a rich and diverse curriculum to meet student needs and some courses (and even some elements within courses) will lend themselves better to a hybrid model than others. Conversations about identifying which aspects work best in a hybrid model will need to take place at different levels, including at a senior level, programme or school level, and by including the students themselves. For example, courses weighted towards more practical elements may need more thought to design in a hybrid model. A student’s individual circumstances will also be another critical factor, if travel options are limited the choice of attending remotely may be appreciated.

Issues around access to technology are likely to be a key factor. We tend to think of technology as the enabler for the remote students in a hybrid model, but it can be just as important for the students attending in person if they are to interact with their remote peers and engage fully in the lesson too.

For FE learners, Jisc has worked closely with the Education Training Foundation (ETF) to develop clear guidance within the digital teaching professional framework focusing on hybrid.

Managing student expectations

Teaching in hybrid contexts may also be new for many students and although providing choice regarding how they experience learning will benefit many, they may need extra support to adapt too. Having a daily routine, making time and space to learn remotely, and considering what works best for each student in light of their other commitments all play a part.

Top tip

The University of Edinburgh’s Academic Support Unit produced study support materials to help students working in hybrid environments. This includes guidance on note taking, taking part in discussion forums and collaborative group working and more. Consult regularly with your students to address their support needs in hybrid contexts.

More vulnerable students are likely to be more at risk of feeling isolated or have other wellbeing concerns if they are participating remotely. Consider how you can build in opportunities for all learners to participate in the session by asking questions, sharing ideas and providing feedback. This could be something as simple as asking both in person and remote learners for their input by contributing via the chat pane or taking the mic.

Timing is key too – checking in with learners at key stages in a course provides them with opportunities to voice any concerns and gives you a valuable temperature check that everyone is on track. Are there any aspects of the course that learners particularly struggle with? Which aspects of the course lend themselves to digital settings where learners can receive instant feedback? New ways of learning need to be scaffolded by other skills in order to increase confidence and improve familiarity with tools and behaviours that will improve the hybrid experience.

Top tip

At the University Of Greenwich, the Academic Support Team run 'preparing to learn online' workshops all year round for students to develop scaffolding skills at the point of their need.

Strategies to engage students in a hybrid model

Effective hybrid learning requires a significant rethink of how learning is structured and planned.

Here are some suggestions to consider:

- Recording appropriate sections of lectures

This can help students who are either struggling or miss a lesson and need to catch up. - Class discussions

These are a staple of many lessons, but are likely to present extra challenges in a hybrid model because of barriers that in person and remote students face when hearing and interacting with each other. Consider how you position webcams and arrange the room so that online people are visible to all. Make sure you check the sound quality for everyone as well – if the sound is poor for the remote people the experience and interaction will suffer. Unless you are fortunate enough to equip every student with a reliable mic you might want to consider how this kind of exchange can be replicated using online discussion forums. Read this infographic from The Open University about the kind of language to employ in an online discussion forum to maximise engagement - Polling

This is a great way of getting immediate feedback from students and is a feature on many of the platforms used by colleges and universities. - Breakout rooms

A great way to encourage interaction and support smaller group work with learners. Large class sizes can present challenges when managing interaction, but learners can often feel more comfortable participating in smaller groups. Read this article from the University College London to find out more about how you could make best use of breakout rooms - Digital library resources and support

This can also greatly improve the student experience in a hybrid model. Providing content, however valuable, is not enough on its own to enable student learning to take place. For many years, academic librarians have been active in the classroom, helping students to develop their information and digital literacies.

Third-party tools

If your existing platforms don’t have the functionality you need, there are a range of external tools available that can help boost engagement. There should be a sound reason to use any tool - not just because it is digital. Poor planning of introducing tools could be counter-productive to the learning.

The important rule to remember is: what do I want the learner to do? Knowing what you are looking for in a tool can help create a shortlist rather than searching without a proper aim. It is also important to find a tool that is a good fit for the job you are looking to fulfil. Be wary of changing the learning to fit around a tool!

Offering support

This can be a challenge, particularly with larger groups of students. Be clear about the best methods of contacting you or the teaching team and the timescales for expecting a response.

Consider having open channels for people asking for help where the learner community can start to build a “knowledge-base”, or a collaborative document that answers common queries. This might help take the pressure off you as an individual and give the community another reason to exist. Learners could even take an active role supporting each other (eg digital ambassadors, group projects).

Also, provide private channels where learners can communicate with you in confidence.

What are the barriers to meeting this challenge?

What are the skills factors?

Can staff meet (are they aware of) accessibility standards?

Making digital content fully accessible can help improve student engagement with learning and improve outcomes.

Accessibility of your digital estate is not only a legal requirement. Content that meets high standards of accessibility is more user-friendly, understandable, and robust in that it will display well across different browsers and devices.

Read our guide on what steps you can take to meet accessibility regulations.

Making digital content fully accessible can help improve student engagement with learning and improve outcomes.

Accessibility of your digital estate is not only a legal requirement. Content that meets high standards of accessibility is more user-friendly, understandable, and robust in that it will display well across different browsers and devices.

Read our guide on what steps you can take to meet accessibility regulations.

What are the motivation factors?

Supporting reluctant staff

Delivering effective hybrid learning may push digitally-shy staff out of their comfort zone, making them reluctant to take part. Consider how support staff can help, often more than one person is required to deliver effective hybrid learning, especially if it is a larger class. You might like to appoint support staff or even students as ‘chat champions’ to help monitor exchanges and troubleshoot.

Equally, digitally confident staff may have the tech knowledge, but find it difficult to address two audiences at the same time.

Consider how good practice in hybrid delivery is shared and celebrated across the institution to help build confidence and participation.

Delivering effective hybrid learning may push digitally-shy staff out of their comfort zone, making them reluctant to take part. Consider how support staff can help, often more than one person is required to deliver effective hybrid learning, especially if it is a larger class. You might like to appoint support staff or even students as ‘chat champions’ to help monitor exchanges and troubleshoot.

Equally, digitally confident staff may have the tech knowledge, but find it difficult to address two audiences at the same time.

Consider how good practice in hybrid delivery is shared and celebrated across the institution to help build confidence and participation.

What are the knowledge factors?

Staff induction

Is staff induction carried out using organisational platforms, tools and techniques demonstrating good practice? Do staff know how others are delivering effective hybrid sessions?

Another approach would be to incorporate good practice into any induction programme for new staff and build this into CPD channels.

Is staff induction carried out using organisational platforms, tools and techniques demonstrating good practice? Do staff know how others are delivering effective hybrid sessions?

Another approach would be to incorporate good practice into any induction programme for new staff and build this into CPD channels.

Online safety

Are you and your students aware of how to report safety, privacy or security concerns? Are there policies in place that are up to date and fit for purpose?

Are you and your students aware of how to report safety, privacy or security concerns? Are there policies in place that are up to date and fit for purpose?

What are the environmental factors?

Access to platforms, equipment and software

Perceptions vary, but one factor that often comes up is whether both staff and students have access to the equipment and connectivity they need.

Perceptions vary, but one factor that often comes up is whether both staff and students have access to the equipment and connectivity they need.

Do staff have access to platforms with the appropriate functionality to deliver effective hybrid learning?

Once these systems have been identified it is worth checking that all staff have the equipment and software required, such as mics and/or headsets, webcams, and sufficient licences for accessing any specialist software.

Once these systems have been identified it is worth checking that all staff have the equipment and software required, such as mics and/or headsets, webcams, and sufficient licences for accessing any specialist software.

Create a culture of experimentation

Create a culture for staff to team teach and explore this emerging methodology; for finding the best combinations that work for different courses, students and individuals.

This could include spaces for staff to discuss, experiment, and “fail fast”, with support from peers and access to mentoring.

Create a culture for staff to team teach and explore this emerging methodology; for finding the best combinations that work for different courses, students and individuals.

This could include spaces for staff to discuss, experiment, and “fail fast”, with support from peers and access to mentoring.

What are the myths associated with this challenge?

Apocryphal stories surround effective hybrid learning, which can often have an unhelpful impact on staff when approaching the topic. Here are a few that might surface in your conversations when discussing effective hybrid learning.

The following myths are worth reflecting and we offer strategies that you can adopt to mitigate them.

Myth: delivering effective hybrid learning involves the latest digital technologies

The allure of shiny new technology is seductive. It’s tempting to think that if we adopt cutting-edge technologies then these things will automatically transform our practice. However, the issue is that using innovative technology doesn’t inevitably make us more innovative. It’s entirely possible to transform practice using the simplest of digital tools.

It’s often better to start with more tried and tested platforms that both staff and students already have a degree of familiarity with. Many staff may feel left behind and lack confidence with technology. It’s important to ensure staff have opportunities to share knowledge, practices and experiences with colleagues.

The allure of shiny new technology is seductive. It’s tempting to think that if we adopt cutting-edge technologies then these things will automatically transform our practice. However, the issue is that using innovative technology doesn’t inevitably make us more innovative. It’s entirely possible to transform practice using the simplest of digital tools.

It’s often better to start with more tried and tested platforms that both staff and students already have a degree of familiarity with. Many staff may feel left behind and lack confidence with technology. It’s important to ensure staff have opportunities to share knowledge, practices and experiences with colleagues.

Myth: young people are “digital natives” and will just “get” how to be part of a learning community online

The critique of Prensky’s Native and Immigrants model is detailed but simply, a familiarity with certain types of technologies in certain contexts does not necessarily translate into using technology to support learning. Age is not the prime determiner.

The critique of Prensky’s Native and Immigrants model is detailed but simply, a familiarity with certain types of technologies in certain contexts does not necessarily translate into using technology to support learning. Age is not the prime determiner.

Scenario five: developing virtual escape rooms for learning

What is the challenge?

Developing virtual escape rooms can help to gamify the learning experience, promote teamwork and make learning fun and rewarding. Although these benefits can be true, the most effective virtual escape rooms need a good degree of planning and testing to get right too. Without proper preparation and implementation, virtual escape rooms can be a source of frustration and even switch learners off.

What are the key issues you need to consider when designing a virtual escape room for learners to ensure a positive and engaging experience?

What questions do you need to ask?

There are many considerations to reflect on when creating your own virtual escape room for learners, these include:

- Start with the learning objectives and work backwards from those. What do you want the learners to know by experiencing a virtual escape room?

- Think beyond the puzzles in the virtual escape room itself. Are there are opportunities for learning with orientation activities beforehand? Debriefs after the escape room attempt also help to reinforce learning and provide opportunities for feedback.

- Are the students familiar with the digital platform you are using for the virtual escape room? How can you set the scene and outline available support in advance? Can you use an institutional platform they are already using?

- Escape rooms should be challenging, but how can you build in support in case students need it? This could be in the form of peer support, clues or building in opportunities to ask staff questions.

- Can you create a compelling story to help contextualise the escape room puzzles? Is there an engaging scenario that will resonate with students? Make students feel part of the story by creating branching narratives. Providing meaningful choices will help to draw learners in!

- Consider how you match the puzzles to the theme or story. Include a range of puzzles too. Variety will challenge and stretch learners in different ways and encourage them to work together.

How can digital support the pedagogy?

Think like a digital storyteller

Virtual escape rooms work best when there’s a convincing story. Be creative and harness storytelling techniques to help immerse learners. Start storyboarding the virtual escape room by first sketching a visual representation of the learner’s journey throughout the escape room.